The President's House in Philadelphia, Part I

Index | Part I | Part II | Revisited

I.

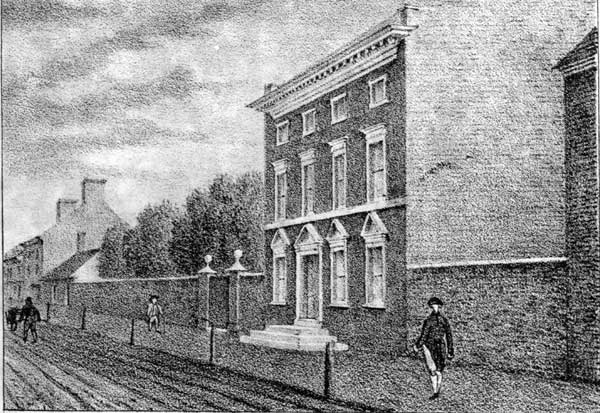

Fig. 1. "Washington's Residence, High Street." Lithograph by William L. Beton. From John Fanning Watson's Annals of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1830), PL. facing p.361. Library Company of Philadelphia. Some copies of the 1830 edition of the Annals have the other Breton lithograph of the President's House.

For more than 150 years, there has been confusion about the President's House in Philadelphia (fig. 1), the building that served as the Executive Mansion of the United States from 1790 to 1800 — the "White House" of George Washington and John Adams. In July 1790 Congress named Philadelphia the temporary national capital for a ten-year period while the new Federal City (now Washington, D. C.) was under construction, and one of the finest houses in Philadelphia was selected for President Washington's residence and office. Prior to its tenure as the President's House, the building had housed other such famous (or infamous) residents as Proprietary Governor Richard Penn, British General Sir William Howe, American General Benedict Arnold, French Consul John Holker, and financier Robert Morris. Historians have long recognized the importance of the house, and many have attempted to tell its story, but most have gotten the facts wrong about how the building looked when Washington and Adams lived there, and even about where it stood.

Beginning around 1850 — fifty years after Washington's death — a dispute arose over the size, the exact location, and the appearance of the building during his presidency. Most of the house had been demolished in the 1830s, and since there seemed to be little physical evidence of it remaining, the disagreement boiled down to the conflicting boyhood memories of two antiquarians: John Fanning Watson and Charles A. Poulson. Each man was well-intentioned, and following what he thought was the truth, but their visions of the house seemed irreconcilable and neither proved his case definitively. Both men had adherents who carried on the debate after their deaths, and the controversy continued without a final resolution for more than a century. In the 1930s, a team under the Works Progress Administration spent close to two years researching the house and constructing an elaborate scale model of it, 1 but their work was based upon a theory that has proven to be specious. The long controversy caused considerable confusion — fiction almost triumphed over fact — and a trail of misinformation about the house developed that has continued to this day. The ultimate casualty of the confusion was the building itself, portions of which survived into the middle of the twentieth century, only to be demolished because they were not recognized for what they were. The purpose of this article is to correct the century-and-a-half of misinformation, to put an end to the confusion, and to present an accurate and documented portrait of the President's House.

The President's House stood on the south side of Market Street between 5th and 6th Streets, less than 600 feet from Independence Hall, on land that is now part of Independence Mall. The soon-to-be-demolished Liberty Bell Pavilion is at the center of the block; the site of the President's House is about 45 feet west of the pavilion, and about 60 feet east of the old building line of 6th Street. Sixth Street has been greatly widened,2 but one can see the old building line and the relative widths of the sidewalks and roadway by looking at the west side of Congress Hall — a block away at the southeast corner of 6th and Chestnut Streets. All of the buildings on the land bordered by Market, Chestnut, 5th and 6th Streets, "the first block of Independence Mall," were demolished in the early 1950s. By modern numbering, the address of the President's House would have been 526-30 Market Street.3

The house has been given many names: The Masters-Penn House4 (after its first two owners), 190 High Street5 (its first eighteenth-century address), the Robert Morris House6 (one of at least seven Philadelphia houses associated with him), the Washington Mansion7 (which gives short shrift to Adams who lived there as president for more than three years), the Executive Mansion, the Presidential Mansion, and multiple variations on the latter two. The name most often used by eighteenth-century newspapers, diarists, and letter-writers — and the name used by Washington and Adams in their formal correspondence — was "President's House." Later, this was the name given to what we now know as the White House in Washington, D. C., but that should not cause confusion.

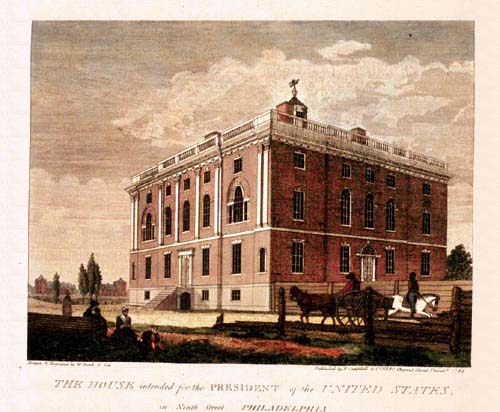

Fig.2. "The House intended for the President of the United States, in Ninth Street, Philadelphia." Both Presidents Washington and Adams declined to occupy this mansion. Engraving by William Russell Birch and Thomas Birch. From The City of Philadelphia...As It Appeared in the Year 1800 (Philadelphia, 1799), pl. 13.

What has caused considerable confusion is mistaking the house for the mansion shown in plate 13 of "Birch's Views" (fig. 2)8 — or, to give the book by William Russell Birch its correct title, The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America; as It Appeared in the Year 1800. The mansion shown in Birch was erected in the 1790s by the city as part of an unsuccessful attempt to induce Congress to change its mind, abandon the District of Columbia, and name Philadelphia the permanent capital of the United States. This mansion was enormous, its main building was about 100 feet square, and it stood on the west side of 9th Street between Market and Chestnut Streets. Both of the first two Presidents declined to occupy the mansion — in Washington's case, even once the building was substantially completed, because he wanted to discourage Philadelphia's efforts to keep the national capital, and in Adams's, because he claimed that he could not afford to live in the mansion on his presidential salary, and he would not be subsidized by the State of Pennsylvania.9

The house the presidents did occupy — Washington from 1790 to 1797, and Adams from 1797 to 1800 — was one of the two or three largest private residences in the City10. Although their contemporaries may have used the name "President's House" interchangeably for both the house and the never-occupied mansion,11 throughout this article it will refer only to the Market (or High) Street house in which Washington and Adams actually lived and worked.

The original house was built by Mary Lawrence Masters, the widow of William L. Masters, for herself and her two daughters, Polly (also Mary) and Sarah. A descendant of Mrs. Masters claimed — in 1913 — that the building had been erected in 1761,12 the year the widow obtained the land, and subsequent authors seem to have accepted this date uncritically. However, the site is open land on the Clarkson-Biddle Map of 1762,13 and tax records indicate that the house was built six to seven years later. In 1756, "William Masters Esquire" was recorded as living in the Lower Delaware Ward,14 the boundaries of which were the Delaware River, Market Street, Front Street and Dock Creek. His residence, The Bank House, stood at the southeast corner of Front and Market Streets, opposite the London Coffee House. He died in 1760, and his widow was listed as living in the same ward in 1765 and 1767, presumably in the same house.15 In December, 1767, Mrs. Masters was taxed on "a New House and Lot in M. W." [Middle Ward],16 but it is not until 1769 that the tax records list Mrs. Masters as living in the Middle Ward — the boundaries of which were Front, Market, 7th and Chestnut Streets. In the tax ledgers the names of the owners of adjacent properties on Market Street between 5th and 6th Streets are adjacent to Mrs. Masters's name, making it almost certain that her new residence was the building that became the President's House. It is likely that the house was under construction in December 1767 and it may have been completed in 1768.17

On May 21, 1772, Mrs. Masters's daughter Polly married Richard Penn, a grandson of William Penn, Pennsylvania's founder, in Philadelphia at Christ Church. Richard Penn was the lieutenant-governor of the colony, and with his elder brother John, the governor, in England, Richard was acting governor. Two days before the nuptials, Mrs. Masters conveyed the title of 526-30 Market Street to Polly as a wedding present.18 Richard Penn moved into the house with his bride, mother-in-law, and then thirteen-year-old sister-in-law. The following year, he had the building insured by the Philadelphia Contributionship. The 1773 insurance survey provides a detailed description of the house:

Surveyd March 1, 1773, Governer Penns dwelling house Situate on the South Side of high Street between 5th & 6th Streets — 45 feet front, 52 feet deep 3 Storys high 14 & 9 inch party walls — 3 rooms Entrey & Stair Case in first Story, one Story of Stairs Rampd & Bracketed wainscuted and a twist — wainscut rails and balisters Mahogony, Stair Case & Entery wainscut pedistal high, 2 fluted Culloms, 4 pillasters, 4 arches, 4 pediments, modilion Cornish — front parlor wainscut all round, 12 pillasters, Cornish InRichd with fretts I dintalls &c, also the Bass & Surbass, 3 pediments, tabernakle frame mantle Cornish &c on Brest — west back parlor wainscut all Round, plain duble Cornish with a frett in bedmold, two pediments, tabernakle frame &c on Brest — East Back parlor Chimney Brest Surbass Scerting & plain dubble cornish — dowel floor in first Story — 3 Mahogony doors — Mahogony sashes in each Story Glass 16 in by 12 in, — front Chamber in 2d Story wainscut pedistall high, frett Cornish, tabernakle frame &c. on Brest — pasage wainscut pedistal high, 3 pediments, Block cornish — west back Chamber the Same as front, but no tabernakle frame on Brest — East back Chamber Chimney Brest Surbass Scerting & dubble Cornish — 3 Story chimney Brests Surbass & Scertings — Garot plasterd 4 Rooms 4 Nich dormers. — Rooff Coverd with Short Shingles — A frontispeice at door, 3 pediments to windows, Modilion Eaves — the whole painted inside & out, a Brick wall Runs north & south in the middle of the house. The Back building 14 by 7 ft & 54 by 18 feet one Story high, 9 inch walls --

£2000 on the House @ 50/ pC£ to be divided in four Parts Viz by the Brick Wall running from Front to Rear and by the Brick Wall running East and West through the Westwardmost Division and an imaginary Line continued from thence to the East Gabel End

On the Backbuildings £300 — 20/ pC£19

This survey makes it clear that Mrs. Masters's house had a four-bay, asymmetrical façade — a bay being a vertically aligned set of openings. Although a popular type in London, a four-bay city house was unusual for the American colonies, and fewer than a dozen examples seem to have been built in pre-revolutionary Philadelphia, none of which survived to the twentieth century. Others included the General John Cadwalader house, the Judge William Coleman house, the Thomas Willing house, and the Edward Shippen house (on 4th Street). An eighteenth-century floorplan for a house similar to Mary Masters's house (possibly the Willing house) is in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and is sometimes attributed to Samuel Rhoads.20

The survey states that the main house was 45 feet wide and 52 feet deep, with the standard 14-inch exterior walls and 9-inch interior walls.21 On the facade of the first story was a frontispiece or decorative architectural frame surrounding the front door that, along with the three windows, bore pediments, or triangular tops. There was a cornice molding at the roof decorated with modillions, a series of ornamental brackets. The roof was covered with wooden shingles, probably cedar, which were laid in tight (short) courses.

The house was, in essence, two adjacent rowhouses. On the first story, the western half contained two large rooms or parlors; the eastern half had the entry, stair hall, and a smaller parlor. The brick wall down the center of the house may have risen all the way to the peak of the roof to help support the ridgepole (the top beam), and it could have functioned as a partial fire wall between the two halves.

For assessment purposes, the main house was divided vertically on its axes by imaginary lines into four parts, with each quarter assigned a single insurance policy. The policies were for £500 each, so the total coverage was £2000, with a premium of 50 shillings per £100 of coverage. A fifth policy on the backbuilding was for £300, with a premium of 20 shillings per £100 of coverage.22

By 1775 the political climate of the colonies was changing, and some sort of conflict with the mother country seemed inevitable. Richard Penn decided to return to England with his wife, mother-in-law and sister-in-law. Before he left, he put his Pennsylvania affairs in the hands of his agent, Tench Francis.

In the late summer of 1777, General Sir William Howe, commander-in-chief of British forces in America, sailed his fleet south from New York City into the Chesapeake Bay, landed in Maryland, then advanced his troops toward Philadelphia. General Washington and the Continental army attacked the British at Brandywine Creek on September 11, but were repulsed. After some skirmishes and a feint to the north, Howe marched into Philadelphia unopposed fifteen days later. Washington made a surprise attack at Germantown (just north of the city) in early October, but this opportunity for a patriot victory turned into a humiliating defeat. It was to be the last major action near Philadelphia until the spring. Washington withdrew to Valley Forge, some twenty miles outside the city.

General Howe moved into Richard Penn's house, and made it both his residence and headquarters. Having captured the de facto capital of the colonies and occupied it with more than ten thousand troops, Howe sat back and waited for the rebellion to fall apart. With little to do, many of the British soldiers passed the time by playing cards and with cockfights and horse races. Some put on plays and concerts and gave balls for the young ladies of the city. The general became the darling of Philadelphia's Loyalists, and the house the center for "high life." The social whirl reached its peak in May 1778 with the Meschianza, an enormously elaborate (and expensive) day-and-night spectacle organized by Howe's officers, and held at one of the suburban villas. By this time, the General had been recalled to England, and this regatta, medieval pageant, casino, ball and banquet, topped off with fireworks, was a send-off not to be forgotten.

But the rebellion had not fallen apart. Howe was replaced by Major General Sir Henry Clinton, a no-nonsense officer, who probably lived in Richard Penn's house for only a month. Clinton had been given instructions from London that the army should abandon Philadelphia and return to New York City. A twelve-mile-long line of troops and civilians (including more than three thousands Loyalists) made the slow journey across New Jersey to New York. The last of the British soldiers crossed the Delaware River on June 18. Philadelphia was reclaimed by the American patriot forces and Richard Penn's house became the residence of the new military governor of the region. A popular but false legend claims that Howe's bed was still warm when taken over by the house's next resident — another lover of high life and arguably the fiercest warrior of the Revolutionary War — Benedict Arnold.

Arnold entered Philadelphia on June 19, 1778 and immediately declared martial law. There is a good deal of confusion about when he moved into Richard Penn's house. Based upon misreadings of nineteenth-century sources, some twentieth-century authors have erroneously claimed that Arnold made his temporary (or permanent) headquarters at the Slate Roof House, the Governor John Penn House (next to the Powel House), and the General John Cadwalader House. The most reliable first-person account of the reentry of the patriot forces into the city is in a letter found in Watson's notes for his Annals of Philadelphia. Deborah Logan states that Arnold initially made his headquarters in the house of Henry Gurney, a retired British Army officer.23 (Gurney's house was on the north side of Chestnut Street between 4th and 5th — opposite what is now the Second Bank; it was later numbered 153 Chestnut.)24 According to Logan, within a week of Arnold's arrival in Philadelphia he had moved from Gurney's house into Richard Penn's house.

General Arnold lived grandly in the Market Street house with his military staff of ten, hiring at least seven servants, and keeping a chariot and four horses. The French ambassador, M. Conrad Alexandre Gérard, arrived in Philadelphia the second week in July, and he and his suite temporarily lodged at the house as Arnold's guests. On July 12, a reception was held there to welcome the new ambassador, which the wife of the Loyalist Joseph Galloway noted in her diary.25 Galloway had bought Alexander Stedman's house, next door to Mrs. Masters, in 1770. Mrs. Galloway remained in Philadelphia after the British evacuation in the vain hope that she could protect the property from confiscation by the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania.

Arnold resigned as military governor on March 19, 1779. That month, he bought a villa outside the City, the heavily-mortgaged and already-tenanted Mount Pleasant, to give to his bride, Peggy Shippen, as a wedding gift. The two were married on April 8, but they lived together in Richard Penn's house for only a couple of months. In May, Arnold began his treasonous correspondence with the British.

All told, Arnold occupied the house for just over a year. By September 1779, he and his wife had moved to a less expensive house owned by her father.26 The following summer, Arnold requested the post of commander of the fort at West Point in New York, with the secret intention of surrendering it to the British. Washington agreed to his request, with results familiar enough not to need recounting.

The next tenant on Market Street was the French Consul John Holker. A merchant and the French-raised son of a British exile, Holker had worked with Benjamin Franklin, secretly providing supplies and money to the Continental army before France officially entered the war. Holker made an enormous amount of money profiteering, and, when later forced to choose between his private business dealings and his official post, chose business. Holker was living in Richard Penn's house when it caught fire on the morning of January 2, 1780.

The fire was recorded by two diarists and a newspaper. Jacob Hiltzheimer wrote: "Early this morning a fire broke out in Mr. Penn's house, on Market Street, occupied by Mr. Holker, the French Consul, which was consumed to the first floor."27 Elizabeth Drinker wrote: "Richd. Penns large House up Market Street took fire last night, and this Morning is consum'd all but ye lower storey."28 The Pennsylvania Packet recorded: "Last Sunday about 7 o'clock in the morning, a fire broke out at the dwelling of the Hon. John Holker, Esquire, in Market-Street, and continued burning for a long time, which did considerable damage, but was happily prevented from spreading any farther..."29

There is no precise evaluation of the severity of the fire and the extent of the damage to the house. This uncertainty has led to speculation by historians that the fire was catastrophic, that the house lay abandoned for years, and that subsequently it was drastically altered. The Hiltzheimer and Drinker diaries agree that the fire consumed the upper two floors and garret, but what they say about the rest has been interpreted to mean everything from the first floor surviving untouched, to the exterior walls of the whole house collapsing to the first floor. The fire was severe enough to cause some damage to the Stedman-Galloway House, 35 feet to the west, but, barring additional contemporaneous accounts, the exact extent of the damage to Richard Penn's house cannot be determined, except to say that the estimated cost of repairing it was in excess of £2000.30 The design and construction of the building should have made it especially resistant to fire. The thick exterior walls and the party wall down the center were all of brick, and could have survived the flames. Matching descriptions of the house in the 1773 insurance survey and in first-person accounts from the 1790s argue strongly that the 1780 fire was not catastrophic, and that Robert Morris, who purchased the building after the fire, rebuilt it to the essentially same plan as before, and within the same walls. No evidence has been found to support the often-repeated claim that the house was so damaged that it was necessary to totally or even partially raze it.31

The deed between Richard Penn et al., and Robert Morris is dated August 25, 1785, and most Morris biographers have made the logical assumption that his rebuilding and occupancy of the house must have occurred subsequent to that date. The deed is thousands of words long and written in a hand which is not always legible, but a close reading of it gives a different chronology: (1) The house burns — January 2, 1780. (2) Richard Penn (by letter) directs Tench Francis to sell the house. Penn had previously given Francis power-of-attorney over his American real estate. (3) Robert Morris enters into a contract with Tench Francis to buy the house for £3,750 to be paid to Richard Penn upon perfecting the title — no later than Spring 1781. (4) Robert Morris takes possession of the house — no later than Spring 1781. (5) Pursuant to the contract between Morris and Francis, an indenture tripartaite (three-part) is drawn up and signed in England in which Richard and Polly Masters Penn, Mary Lawrence Masters, and Sarah Masters convey the property to Tench Francis so he may sell it — June 8, 1781. (6) The indenture tripartaite is recorded in Philadelphia — December 21, 1781.32 (7) Morris is dissatisfied with the description of the property in the indenture tripartaite. His legal counsel advises that a deed which better describes the property be executed by all the parties. (8) The new deed is recorded in Philadelphia — August 25, 1785.33

The 1785 deed states that the 1781 indenture tripartaite was drawn up in response to a sales contract between Morris and Tench Francis. This contract has not been found, but in order for it (or news of it) to have reached England by June 8, 1781 it must have been signed in America no later than April 1781. Had the indenture tripartaite been satisfactory to Morris, it would have become the basis for the new deed, and December 21, 1781, might have been his settlement date on the house. In the more than six months between the time when the indenture was signed in England and when it was registered in Philadelphia, the Seige of Yorktown had taken place and General Cornwallis had surrendered. It is likely that it was during this same period, perhaps beginning as soon as the sales contract was signed, that Morris had the house rebuilt.

Morris's possession of the property as of August 8, 1781 is confirmed by an advertisement printed in two Philadelphia newspapers (italics added):

To be Sold by Public Auction,

At the COFFEE-HOUSE on TUESDAY next, the 14th of

August, at TWELVE o'clock noon,

A LOT of Ground. Situate on

the South side of Market-Street, between Fifth

and Sixth Streets, adjoining the walled lot, lately Richard

Penn, Esquire's, but now Robert Morris, Esquire's, contain-

ing in breadth 24 feet on Market-Street, and extending 180

feet in depth to Minor-Street, a new street 40 feet wide. The

purchaser may be accomodated [sic] at a reasonable price with

a lot of ground of the same width to the southward of Minor-

Street, opposite to the above, and 86 feet deep; which price

may be known of JAMES, PHILIP, or THOMAS KINSEY.

August 8, 1781.34

This auction may never have taken place, for two months later the Kinseys sold the lot to be auctioned (522 Market Street) and the adjacent lot (520 Market Street) together as a single 49 x 180-foot parcel to Robert Morris for £1837/10.35 Over the next few years, Morris also bought 516-18 Market Street36 and 514 Market Street.37 He turned these lots into a walled garden of slightly less than a half an acre. Morris later bought the State House Inn property on Chestnut Street38 (directly opposite Independence Hall), which ran north to Minor Street.39

Morris's possession of the Masters-Penn property in August 1781 can also be confirmed through tax records. In November 1780, the property was listed under Tench Francis's name as Richard Penn's estate, which was taxed £330 on a valuation of £120,000.40 In August 1781, it was Morris who was taxed at this location for £40/5/0 on a valuation of £350041. This valuation is quite close to the £3750 that Morris offered (and eventually paid) for the fire-damaged house. The following year, Morris was again taxed at this location for £31 on an assessed valuation of £600042. This dramatic increase in valuation over one year may reflect both the rebuilding of the house and the addition of 520-22 Market Street to the property.

On August 30, 1781, General Washington, Lieutenant-General Comte de Rochambeau (commander of the French forces), and their troops arrived in Philadelphia on their way to Yorktown for what would become the final battle of the war. Both generals and their officers were entertained that night by Robert Morris at his house on Front Street. Washington and his staff moved into this house, making it their headquarters and lodgings for about a week.43 One of the guests at Morris's August 30th dinner, French General Chevalier (later Marquis) de Chastellux, kept a journal, the first part of which had been privately printed in French earlier that summer in Newport, Rhode Island. A British exile named George Grieve visited America a couple of months after the Seige of Yorktown, and subsequently made an unauthorized English translation of Chastellux's journal. In his translation, Grieve erroneously claimed that Morris's dinner with Washington, Rochambeau and Chastellux had taken place at the house on Market Street. Although Grieve's assumption about the location of the dinner was wrong, the very fact that he made this mistake would argue that the house was no longer fire-damaged, that the rebuilding had been completed, and that it was, or appeared to be, habitable. Grieve's brief reference to the Market Street house reflects, presumably, exactly what he saw in Philadelphia in early 1782 (italics added): "The house the Marquis speaks of, in which Mr. Morris lives, belonged formerly to Mr. Richard Penn; the Financier has made great additions to it, and is the first who has introduced the luxury of hot-houses, and ice-houses on the continent."44

Grieve's mention of an icehouse and his observation that Morris was in possession of the property are confirmed by a contemporaneous entry in Hiltzheimer's diary (italics added): "Feb 12. [1782] — Loaned Robert Erwin a wagon and two horses to assist in bringing ice from the Schuylkill [River] to the ice-house of Robert Morris in the rear of his house on Market Street."45 Construction of the icehouse was therefore complete in February 1782 and occupancy of the residence had either begun (as Grieve states) or was imminent (the Morrises stocking the icehouse in midwinter in anticipation of soon moving into the rebuilt house). Two months later, Morris made arrangements to move his office more than seven blocks (about half a mile), from Front Street, south of Dock — next door to his old house — to the northwest corner of 5th and Market Streets — less than 400 feet from his new house.46 None of this pinpoints exactly when the Morrises moved in, but it does overturn the twentieth-century conventional wisdom that Morris didn't rebuild and occupy the Richard Penn house until 1785 or later.

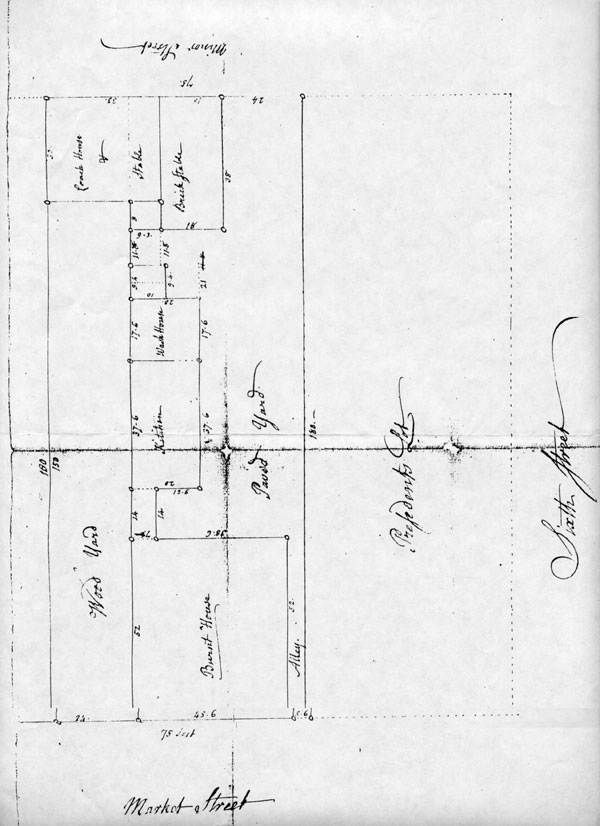

Fig. 3.. "Richd Penn's Burnt House Lott — Philadelphia." This groundplan seems to show the property as it was in 1781 when Robert Morris contracted to buy it, although he did not obtain full title ot the property until 1785. North is toward the bottom. Unknown draftsman, ca. 1785. RG-17 Land Office Map Collection, Pennsylvania State Archives.

The August 1785 Penn-Morris deed included a groundplan of the property (fig. 3),47 which is consistent with both the 1773 insurance survey and later descriptions of the house from the 1790s during Washington's presidency. The groundplan shows a "Burnt House" attached by a piazza to a backbuilding containing a "Kitchen" and "Wash House." Attached to the south wall of the wash house is the smokehouse. Less than a dozen feet south of this is the cow house, which is attached to a "Brick Stable," and a "Coach House & Stable" (of wood?) on "Minor Street."48 To the east (left) of the house is the walled lot (524 Market Street), labeled "Wood Yard," which was used for storing firewood, and making deliveries to the kitchen. The almost-half-acre walled garden (514-22 Market Street) is not shown on the groundplan, but it was adjacent to the wood yard on the east. To the south of the main house is a "Paved Yard" that was used for outdoor entertaining. The Stedman-Galloway property to the west (right) was indeed seized from Mrs. Galloway in 1778, and it became the residence of the president of the Supreme Executive Council — the equivalent of the governor of Pennsylvania (hence the label "Presidents Lot.") Morris bought the Stedman-Galloway House in 1786,49 and seems to have made a common back yard for the two properties,50 although until this purchase there probably had been a fence or wall between them.

It is likely that this groundplan actually shows the property as it had looked in 1781 when Morris took possession of it, since the icehouse and other additions he is known to have made do not appear on the plan. The groundplan also does not show the hothouses recorded by Grieve, perhaps since the logical site for them would have been in the walled garden. A second story was added to the backbuilding some time after 1773, probably by Morris at the same time he rebuilt the main house. He built a two-story addition to the east side of the backbuilding, a bath house — perhaps the first in Philadelphia — that included a bathingroom on each story.

George Washington was a frequent houseguest of the Morrises in the Market Street house, including a four-month stay in the summer of 1787 during the Constitutional Convention. In 1790, Robert Morris, now a U.S. Senator, was instrumental in persuading Congress to name Philadelphia the temporary capital of the United States for a ten-year period while the new Federal City was being built on the banks of the Potomac. When no more suitable house in Philadelphia could be obtained, Morris agreed to move into the Stedman-Galloway House next door and offered his own residence to serve as the President's House. While staying in Philadelphia in September 1790, Washington wrote to his secretary, Tobias Lear, describing Morris's house and giving instructions for its enlargement:

"The house of Mr R. Morris had, previous to my arrival, been taken by the Corporation [the city of Philadelphia] for my Residence. — It is the best they could get. — It is, I believe, the best Single house in the City; yet without additions, it is inadequate to the commodious accommodation of my family. — These, I believe will be made. "The first floor contains only two public Rooms (except one for the upper Servants). — The second floor will have two public (drawing) Rooms & with the aid of one Room with a partition in it, in the back building, will be sufficient for the accommodation of Mrs Washington & the children & their maids — besides affording me a small place for a private study & dressing Room. — The third story will furnish you & Mrs Lear with a good lodging Room — a public Office (for there is no place below for one) and two Rooms for the Gentlemen of the family [Washington's office staff]. — The Garret has four good Rooms which must serve Mr and Mrs Hyde [the steward and his wife] (unless they should prefer the Room over the wash House), — William [Osborne, the valet] — and such Servants as it may not be better to place in the addition (as proposed) to the Back building. — There is a room over the Stable (without a fireplace, but by means of a Stove) may serve the Coachman & Postillions; — and there is a smoke House, which possibly may be more useful to me for the accommodation of Servants, than for the Smoking of Meat. — The intention of the addition to the Back building is to provide a Servants Hall, and one or two (as it will afford) lodging Rooms for the Servants, especially those who are coupled. — There is a very good Wash House adjoining the Kitchen (under one of the Rooms already mentioned). — There are good Stables, but for 12 Horses only, and a Coach House which will hold all of my Carriages . . . "In a fortnight or 20 days from this time, it is expected Mr Morris will have removed out of the House. — It is proposed to add Bow Windows to the two public Rooms in the South front of the House, — But as all the other apartments will be close & secure the sooner after that time you can be in the House, with the furniture, the better, that you may be well fixed and see how matters go during my absence."51

The presidential entourage had arrived in the city several days earlier, and was about to depart for Mount Vernon. It is likely that Morris and Washington spent some of that time going over the house, planning the alterations and additions that would be necessary to convert it into the President's House. Washington was credited as the author of the changes to the building, and although this may have been flattery, he is known to have had a keen interest in and talent for architecture, as demonstrated at Mount Vernon.

The city initially leased Morris's house for two years, during which time a grand mansion for the President was to be constructed (ultimately built on 9th Street), as part of the overall scheme to keep the national capital in Philadelphia. Morris assembled a crew of workmen "to complete the Additions & Alterations pointed out by the President" to the Market Street house, along with any changes to the Stedman-Galloway House made necessary by the Morrises' removal there. This was a "sweetheart" deal for Morris — the city advancing him the money to pay for the alterations to both houses, plus other expenses, with the total to be deducted from the future rent to be paid on his former residence.52 Fortunately for posterity, there were problems with the additions and alterations to the President's House, and a couple of changes in plan, all documented by Tobias Lear in a series of twice-weekly letters written to Washington at Mount Vernon between September and November 1790.

The most dramatic addition ordered by Washington was the construction of a large, two-story bow on the western half of the south façade of the main house. Built by or under the supervision of "Master Mason, Mr. Wallace,"53 the exterior of the bow was constructed of brick with stonework over the second-story windows, and it had an iron roof. While the interior of this bow was curved or semi-circular, no precise documentation has been found as to whether the exterior was semi-circular or semi-octagonal.54 Bows and semi-octagonal bays were a new and fashionable addition to a building. Congress Hall and the Supreme Court Building (on either side of Independence Hall) had been built with bays, and villas such as The Woodlands (and, later, Lemon Hill) possessed bows. Other Philadelphia city houses to which bows or bays were added include the Powel House, the Stedman-Galloway House (possibly the following year, by Morris), and the Stamper-Blackwell House. All these may have been inspired by Washington's bow. The bow of the President's House in Philadelphia is considered the progenitor of the oval rooms at the center of The White House.55

If the 1773 insurance survey is exact in its description, each of the rooms in the western half of the first two stories was just over 24 feet in length (about 24½ feet north-south from brick wall to brick wall, minus the thickness of the interior plastering or paneling).56 The width of the rooms in the western half of the house was just over 21 feet.57 According to Tobias Lear: "When the Bow Window is run up it will make the large dining room and the drawing room over it thirty-four feet long."58 Assuming that Lear was correct, and that the bow truly was semi-circular, this would mean that Washington's bow was about 19 feet in diameter on its interior, adding about 9½ feet to the length of the rear rooms of the first and second stories at their centers.

Washington had the bathtubs removed from the second floor of the 15 x 21-foot (probably interior dimensions) bath house, and had the bathingroom converted into his private office/dressing room/study. Within a week of his moving in he added a "cast [iron] stove & pipe."59 The room must have been hot in the summer, for he later added awnings to the windows.60 More details about the room can be found in a letter from Abigail Adams written when she and her husband occupied the President's House:

"I find the best time for writing, is to rise about an hour earlier than the rest of the family; go into the Presidents Room, and apply myself to my pen. Now the weather grows warmer I can do it. His Room in which I now write has three larg[e] windows to the South. The sun visits it with his earliest beams at the East window, and Cheers it the whole day in winter."61

For privacy's sake, the north wall of the former bathingroom may not have had windows. The iron stove probably stood at the southwest corner (the evidence for this is presented in the October 2005 sequel to this article). The large windows on the east and south walls looked out into the walled garden and stable yard. (In winter, Washington would have had a commanding view of Independence Hall; obscured in summer by the walnut trees surrounding the State House Inn.) One entered the room through a door on the west wall. Washington's Presidential desk from Philadelphia (now in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania collection at the Atwater Kent Museum) was in this room,62 as, most likely, were the globe, the revolving desk chair, and other furniture now in the Library at Mount Vernon. Washington called this room his "study," Abigail Adams and Tobias Lear called it the "President's Room," and John Adams called it his "cabinet."63

Washington added a servants' hall to the east side of the backbuilding in the enclosed area between the bath house and the wall of the stable yard. This long one-story building, 51 x 15 feet (interior dimensions), was described as "another kitchen" in the 1798 insurance policies, and probably served as a work area and eating area for the servants. Washington's intention had been to carve two small lodging rooms out of the south end of the servants' hall, and Lear suggested the construction of a new steward's room at its north end. There is no reason to think that these rooms were not built within the servants' hall, but there is also no documentation confirming it. Initially, the President had planned to house the stablehands in the hayloft over the brick stable, but, when this proved infeasible, he approved Lear's suggestion: "The Smoke-House will be extended to the end of the Stable, and two good rooms made in it for the accomodation of the Stablepeople."64

The "Stablepeople" accommodated in the smokehouse and its addition included enslaved Africans from Mount Vernon. Washington generally had a domestic staff in Philadelphia of between twenty and twenty-four — of these, the number of enslaved Africans ranged from eight at the beginning of his tenure in the city to two or three at the end of it.65 Mid-twentieth-century historians have sometimes ignored or downplayed this fact, but Washington held enslaved Africans in the President's House for the whole time he lived in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania had enacted a gradual abolition law in 1780 — the first former colony to do so — but the statute specifically exempted members of Congress and their personal slaves. Washington regarded himself as a citizen of Virginia, and argued that his presence in Pennsylvania was a necessary consequence of Philadelphia's being the temporary national capital. He was careful not to spend six continuous months in the state (the period necessary to establish legal residency), and rotated his enslaved Africans out of Pennsylvania to prevent their establishing residency. This rotation of the enslaved Africans was itself a violation of Pennsylvania law, and should have resulted in their immediate manumission, but the state law was not enforced regarding the President. Most of the enslaved Africans were replaced by German indentured servants. Slavery was legal in every state but Massachusetts in 1790, and evidently it was not uncommon for members of Congress and other government officials to possess enslaved Africans in Philadelphia.66

In October 1790, Tobias Lear oversaw the moving of the furniture from New York, and directed its installation67 in Philadelphia. He was a meticulous and highly-efficient secretary, and his twice-weekly letters to Washington are filled with progress reports on the alterations to Morris's house, suggestions about where to place furniture and house people, and confirmations that the President's instructions were being carried out.

From Lear's detailed descriptions, the 1773 insurance survey, the 1798 insurance policies, and first-person accounts, it is possible to assemble a reasonably complete floor plan of the President's House at the time Washington lived in it (fig. 4).68

Fig. 4. Conjectural floorplan of the President's House in Philadelphia — first floor. The two-story bow on the south side of the main house, the servants' hall and the slave quarters were all added by George Washington in 1790. North is toward the bottom. ©2001-2005 Edward Lawler, Jr. All rights reserved.

A long passage extended the length of the house from the front door to the back door. The Viscount de Chateaubriand, who visited Philadelphia in 1791, sniffed that the President's House didn't have a proper entrance hall: "A young servant girl . . . walked before me through one of those long narrow corridors which serve as a vestibule in English houses; she showed me into a parlor, where she asked me to await the General."69

The 1773 insurance survey describes the "Entrey" as having four arches, two fluted columns and four pilasters. Several floor plans for houses with a similar entrance hall and passage can be found in a 1757 English pattern book.70 The American house whose entrance passage and hall probably most resembles that of the President's House is "Widehall" (1769) in Chestertown, Maryland (fig. 5). The specific architectural details may have been slightly different, but the Chestertown house gives a good idea of the elegant and dramatic effect of walking through the front door into the arcaded passage of the Philadelphia house.

Fig. 5. Hall and passage of "Widehall" (ca. 1769) in Chestertown, Maryland. Photo by Albert Kruse, April 24, 1934. Historic American Building Survey, no. MD-550.

Widehall's staircase is an open-newel type, ascending in three flights from the first story to the second. The WPA researchers, Harold Eberlein and others mistakenly concluded that the staircase of the President's House had been of a similar configuration, but this conjecture is contradicted by Washington himself. In one letter, the President complained that his office for public business had to be on the third story (italics added): "[Visitors] will have to ascend two pair of Stairs, and to pass by the public rooms, as well as private Chambers, to get to it ..."71

A flight of stairs rising southward along the east wall from the first story to a landing, and a half-flight running perpendicular from the landing to the second story is the solution that is most consistent with the descriptions of Washington, Thomas Twining, and others.72 A mahogany balustrade in the Upper Hall would have defined a central three-story well of space reminiscent of the hall at Shirley Plantation in Virginia, with its famous "Flying Staircase" (Fig. 6.) Robert Morris lent Washington the large glass lamp that hung in the Hall, which was probably suspended on a long chain from the third-floor ceiling. The staircase continued upward in the same manner from the second floor to the public business office on the third.

The height from the Hall floor to the third-floor ceiling would have been about 38 feet, making this an exceptionally dramatic space. An entry from the diary of John Quincy Adams chronicles how the Hall was used on one occasion:

"By the invitation of the President, I attended the reception he gave to Piomingo and a number of other Chickasaw Indians. Five Chiefs, seven Warriors, four boys and an interpreter constituted the Company. As soon as the whole were seated the ceremony of smoking began. A large East Indian pipe was placed in the middle of the Hall. The tube which appeared to be of leather, was twelve to fifteen feet in length. The President began and after two or three whiffs, passed the tube to Piomingo; he to the next chief, and so all around ..."73

One approached the house's front door by climbing a wide stoop of three white stone (reportedly marble) steps, tapering in size. The door probably had lights or windows above it, possibly the fanlight reportedly removed from the house by Nathaniel Burt in 1832, and mentioned by his great-grandson.74 A knob to the side rang the doorbell. The inside of the front door had an iron lock and several iron bolts (these were donated to HSP by the Burt family in the 1950s). Stepping up another step and over the threshhold, one entered the passage which was almost fifty feet in length and carpeted in green, probably bisected by an arch resting on pilasters like the entrances of the Powel House and Widehall. At the far end of the passage was the door to the paved yard, which also may have had windows above it. The passage had painted wainscoting to a pedestal height, and the walls above it were probably painted until Washington had the passage papered in October 1796.75 There were three mahogany doors with pedimented doorways, one near and on the right leading into the family dining room; the other two on either side of the far half of the passage leading into the steward's room on the left, and the State Dining Room on the right. The 1773 insurance survey lists a fourth pediment, that probably was over the interior of the rear door. The passage had a modillion cornice.

Like Widehall, on the left would have been an arcade of three arches, these resting on two pilasters and two fluted columns. The green carpeting of the passage continued into the hall and up the stairs. An ornate heating stove (also lent by Morris) would have been in the northeast corner. The hall was lighted by a single tall, mahogany window on the north wall, decorated with blue damask curtains. The painted wainscoting continued around the hall until the stairs, where it met the mahogany wainscoting of the staircase. At the bottom of the staircase was a "twist" — the mahogany railing and balusters ending in a spiral instead of a newel post. The ends of each step were decorated with an ornamental scroll, or bracket. The railing and wainscoting of the staircase were "ramped," meaning they curved upward to meet those of the landing. The "house clock," probably a grandfather's clock, stood on the first-floor landing and would have been visible throughout both the Hall and Upper Hall.

To the south of the Hall and staircase was the steward's room, that had a plain chimneybreast on the east wall, a single narrow window on the south wall, and doors to the cellar and the piazza. There were closets (under the landing?) in which the china, silver, and liquor could be locked. Washington had considered using this room as the office for the upper servants, but Lear recommended against it.76

The family dining room at the front of the house was about 24 x 21 feet, with wood paneling from floor to ceiling all around, including twelve pilasters, and a chimneybreast on the west wall with a mantel and tabernacle frame above it. There were pedimented doorways on the east and south walls, and, on the north wall, two tall mahogany windows decorated with blue damask curtains. According to the 1773 insurance survey, the room had a third pediment (which must have crowned the tabernacle frame), with a cornice above it decorated with fretwork. This probably was the most ornate room in the house that Mary Masters built, and it may have had a ceiling of decorative plasterwork.77 Washington's "blue furniture" from New York was placed in this room, which included a set of dining chairs (probably those now in the HSP collection at the Atwater Kent Museum), and perhaps a pair of upholstered benches. A pier-glass mirror (lent by Morris, possibly the one now on display at the White House), may have hung between the windows. A breakfast table (possibly the one at Mount Vernon) was used for all the family's meals but the formal dinners.78 It was in this room that Washington's guests waited on Tuesday afternoons for his three o'clock levees, or formal audiences, to begin.

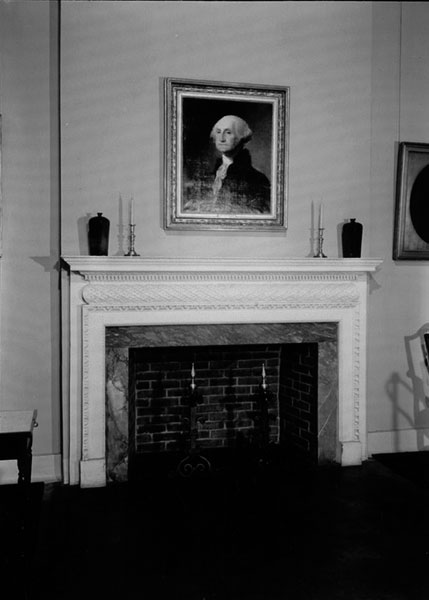

An "unfolding door," perhaps a pair of narrow French doors, separated the family dining room and the State Dining Room. The guests on levee day would pass through the doorway and see Washington — looking much as he does in Gilbert Stuart's Lansdowne portraits — standing some 30 feet away in the bow at the south end of the State dining room framed by three tall windows decorated with crimson damask. With the sun behind him, the effect must have been striking. According to the 1773 insurance survey, the rear room also had floor-to-ceiling paneling and a chimneybreast with a tabernacle frame but no mantel, a cornice decorated with fretwork, and pediments over the doors to the passage and the front room. The whole ceiling of the State Dining Room was replaced when the bow was added in November 1790, as was the ceiling of the State Drawing Room above it, and no evidence has been found that the new one had ornamental plasterwork.

A large carpet with a center medallion of the Great Seal of the United States — made for the State Dining Room by William Peter Sprague of Philadelphia in 1791 — covered the floor.79 This was presumed to have been the carpet in the collection of Mount Vernon since 1897, although recent scholarship suggests that it is not.80 Down the center of the room was a long table — or rather a series of drop-leaf tables which connected to make a single table, with semi-circular end tables, which sat more than thirty. The plateau (now at Mount Vernon), a set of seven low, rectangular, mirrored pedestals (24 x 18 inches and about 3 inches tall) plus two rounded end sections, ran down the middle of the table. Upon this, at State dinners, were displayed a dozen French biscuit-porcelain figurines, along with vases of flowers and candelabra. The furnishings of the room included a pair of "circular" (curved–front) sideboards with large mirrors over them, which probably flanked the chimneybreast. Three large biscuit-porcelain figurine groups, including one called "Apollo Instructing the Shepherds," stood on the sideboards under glass covers. About three dozen dining chairs, probably upholstered in the same crimson damask as the curtains, normally were in the room. These were removed for the weekly levees, and it is likely that the tables were also either removed, or moved to the perimeter of the room with their leaves folded down for ceremonial occasions.

A famous account of what it was like to attend one of Washington's levees in Philadelphia comes from a book called Familiar Letters on Public Characters, written anonymously, and published in 1834:

"[Washington] devoted one hour every other [sic] Tuesday, from three to four, to these visits. He understood himself to be visited as the President of the United States, and not on his own account. He was not to be seen by any body and every body; but required that every one who came should be introduced by his Secretary, or by some gentleman, whom he himself knew. He lived on the south side of Chestnut Street [sic], just below Sixth. The place of reception was the dining room in the rear, twenty-five or thirty feet [sic] in length, including the bow projecting into the garden. At three o'clock, or at any time within a quarter of an hour afterwards, the visiter was conducted to this dining room, from which all seats had been removed for the time. On entering he saw the manly figure of Washington clad in black velvet; his hair in full dress, powdered and gathered behind in a large silk bag; yellow gloves on his hands holding a cocked hat with a cockade in it, and the edges adorned with a black feather about an inch deep. He wore knee and shoe buckles; and a long sword, with a finely wrought and polished steel blade, and appearing from under the folds behind. The scabbard was white polished leather.

"He stood always in front of the fire-place [sic], with his face towards the door of entrance. The visiter was conducted to him, and he required to have the name so distinctly pronounced, that he could hear it. He received his visiter with a dignified bow, while his hands were so disposed of as to indicate that the salutation was not to be accompanied with shaking hands. As visiters came in, they formed a circle around the room. At a quarter past three, the door was closed, and the circle was formed for that day. He then began on the right, and spoke to each visiter, calling him by name, and exchanging a few words with him. When he had completed his circuit, he resumed his first position, and the visiters approached him, in succession, bowed and retired. By four o'clock this ceremony was over."81

This is the most complete description of a levee at the President's House, but its inaccuracies suggest that it may not have been that of an eyewitness. Its author, William Sullivan (1774-1839), was a Boston lawyer whose anonymous newspaper pieces on American history were collected in the book. According to a posthumous biographical sketch by his son in a later edition of the book, Sullivan's (only?) visit to Philadelphia was as a law student in 1795.

Even if he may not have attended a presidential levee himself, the level of detail in Sullivan's account leads one to believe that he got his information from people who had actually been there. His major error (besides locating the President's House on Chestnut Street) was placing Washington in front of the fireplace, rather than in front of the windows of the bow.82 Sullivan's account was quoted in the 1844 second edition of Watson's Annals (and all subsequent editions), Griswold's The Republican Court, and dozens of other books.

What is more likely to be a first-person account can be found in the recollections of Judge John B. Wallace: "Washington received his guests, standing between the windows in his back drawing-room. The company, entering a front room and passing through an unfolding door, made their salutations to the President, and turning off, stood on one side."83

The State Dining Room was also called the "Reception Room" or the "Audience Room," (John Adams called it the "Levee Room") since it was where formal ceremonies involving the President of the United States took place. Congress met in three sessions each year, and Washington would open each session with a speech at Congress Hall, a building some 600 feet south of the house. The Senate would return the visit and offer the President its compliments at the President's House, as would the House of Representatives in a separate visit. (This practice of reciprocal visits was ended by President Jefferson.) Formal ceremonies between nations, such as an ambassador presenting his credentials, would have been performed in this room, including receiving representatives of Native American tribes. According to the secretary to the British minister, the key to the Bastille, given to Washington by Lafayette (now at Mount Vernon), hung in this room, opposite a picture of Louis XVI.84 On at least one occasion during the Adams' tenancy, the rug was rolled up, the tables were removed, and the room was used for a dance for the president's children and their friends.85

Open houses were held at the President's House on New Year's Day and, during Washington's tenure, on the president's birthday. On these occasions, there could be several hundred guests.86 Abigail Adams predicted that the number of people attending an afternoon open house on the Fourth of July would exceed a thousand.87

The second story of the main house had essentially the same floor plan as the first (fig. 7). The upper hall and passage contained mahogany windows, and were wainscoted and finished like the story below. These areas provided ample circulation space, plus room for the overflow crowds which sometimes attended the open houses and the evening receptions or "drawingrooms."

Fig. 7. Conjectural floorplan of the President's House in Philadelphia — second floor. The President's Room, formerly a bathingroom, served as the private office/study (and problaby Cabinet room) for Washington and Adams. North is toward the bottom. ©2001-2005 Edward Lawler, Jr. All rights reserved.

The yellow drawing room (over the family dining room) got its name from the "yellow furniture" from New York that was installed here. This room seems to have been altered by Morris after the 1780 fire, since the 1773 insurance survey lists a chimneybreast with a tabernacle frame, and no mention of a mantel; but the Burt family tradition (published as early as 1875) maintains that the mantel that Nathaniel Burt salvaged from the house in 1832 came from this room (fig. 8).88

Fig. 8. Mantelpiece (ca.1781) from the President's House at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. It is currently on loan to Mount Vernon. Photo by Jack E. Boucher, ca.1965. Historic American Buildings Survey, no. PA-1942.

The mantel's pulvinated (pillow-shaped) frieze of banded foliage — in this case oak leaves — was an extremely rare decorative feature in the colonies, probably because of the complexity and expense of the carving. Not many more than a dozen eighteenth-century examples of this decoration are extant in America. Before the Revolution, the feature is most often associated with the virtuoso carving work of William Buckland (1734-1774), in and near Annapolis.

The mantel is one of two extant examples of a pulvinated frieze of banded foliage used in a Philadelphia house before 1800. The second example, the pediment of the doorway in the library of The Solitude (1784-85), the villa of John Penn "of Stoke" (cousin to Governor John and Richard Penn), was probably carved only three to four years later than the President's House mantel. The decoration of the doorway is so similar to that of the Burt mantel that the two look as if they could have come from the same room and it is possible that they were carved by the same artisan.89

The intricately-carved mantel may give a clue as to the level of decoration in the yellow drawing room, and, indeed, perhaps that of the whole second floor of the house. If all of the doorways in the public spaces in this story had similar pulvinated friezes of banded foliage, there would have been a total of seven of them. This feature might also have been used in the chimneybreast, or in a mantel in the State Drawing Room.

Lear wrote to Washington that there were three sets of yellow damask curtains from the New York house, and suggested that if an additional set were made, the four could serve for all of the second-story windows facing Market Street. The household account books indicate that two additional sets of yellow moreen curtains were purchased,90 which could have freed a set to cover the (presumed) window at the south end of the passage. According to an inventory made by Washington in 1797, a large number of pieces of furniture were upholstered in yellow damask — three sofas, two armchairs, ten sidechairs — and the assumption has been that they were all in the yellow drawing room. (If so, it must have looked like a furniture warehouse.) It is likely that some of this "yellow furniture" would have been spread throughout the Upper Hall and passage.

Additional furniture in the yellow drawing room included two "fixed side boards" (built-in?) bought from the Comte de Moustier, Nelly Custis's harpsichord (now at Mount Vernon) which arrived from London in 1793, perhaps the fortepiano which was destroyed at Mount Vernon by souvenir seekers during the Civil War, a tea table, a large china assemblage called the "Pagoda," and a mirror (lent by the Morrises?). The room had a carpet which in the summer was replaced by rattan matting. According to George Washington Parke Custis, the walls of the room were papered.91 Thomas Twining, who visited on May 13, 1796, described the room: "[I] was shown into a middling-sized, well-furnished drawing room on the left of the passage. Nearly opposite the door was the fireplace, with a wood-fire in it. The floor was carpeted. On the left of the fireplace was a sofa, which sloped across the room. There were no pictures on the walls, no ornaments on the chimney-piece. Two windows on the right of the entrance looked into the street."92

The yellow drawing room was the room into which visitors during the day were generally shown, and the one in which Mrs. Washington served afternoon tea. It is also where refreshments were served for the Friday evening "drawingrooms."93

The State Drawing Room would have been the same size and configuration as the State Dining Room below it — 34 feet from the doorway to the center of the bow. The curtains on the windows and the upholstery of the French-styled furniture throughout the room were green. There was a large carpet (also green?) from Berry & Rogers in New York. At the center of the room hung a large eight-armed chandelier.

Three categories of furniture were used in the President's House in Philadelphia during Washington's tenure: (1) his own private furniture, (2) the Government Furniture (mostly furniture from the Franklin house in New York) which had been bought by Congress for the president's use,94 and (3) furniture Washington bought to supplement the Government Furniture. Much of the latter was purchased in early 1790, and had belonged to the French minister, the Comte de Moustier, who had been the tenant in the Macomb house in New York before the president moved there. Near the end of Washington's second term in office he made an inventory of most of the contents of the Philadelphia house. Included in this was a list of:

| Articles in the Green Drawing Room which will be sold. | |||

| Priced cost | |||

| A Lustre of 8 lights perfect + in no respect injd by use not at all injured | £76 | – 13 | – 0 |

| 3 Green silk Window Curtains rich & liner [illeg.] Drapery etc. | 78 | – 0 | – 0 |

| 2 Brackets oval Mirrors – highly Ornamented | 19 | – | – |

| 1 Sopha of Green Flowered damask with two Cushions | 30 | – | – |

| 12 Arm Chairs — Gr. Set [?] Do Do | 77 | – 0 | – 0 |

| 6 Small Do Do Do | 24 | – 0 | – |

| 6 Do Do Do Do | 24 | – 15 | – 0 |

| 2 Round Stools Do Do | 5 | – 5 | – 0 |

| Carved + gilt flower for lustre | – | – 15 | |

| Two Tafsels for do 15 Chain for Do + gildings | 11 | – 3 | – |

| Carpet | 92 | – 8 | – 0 |

| Articles in the above Room Which may be purchased although the sale of them is not desired | |||

| 2 large looking glafses very cheap at what they cost — exactly such from enquiry — I cannot get for lefs than 300 dollars | 92 | – 0 | – 0 |

| 2 la[rge] brackets + oval Mirrors highly ornamented | 19 | – | – |

| 1 pr of Lustres, two lights each | 20 | – 0 | – 0 |

| 4 Mirrors + pictures suspended to them for Lamps @ 70/ | 14 | – 0 | – 0 |

| 2 pair real Patent Lamps for Ditto pr Jos Anthony's acc. 100 Drs | 37 | – 10 | – 0 |

| 2 Landscapes — 1 Representing a view of the Pafsage of the Potok thro' the bleu mountain, at the confluence of that River with the Shanh — The other at the F[ederal]. City. — cost me with the frames 30 Guineas95 | 52 | – 10 | – 0 |

Many of the pieces listed here still exist, and a number of them are at Mount Vernon, including one pair of oval mirrors and brackets (probably made by James Reynolds of Philadelphia), one of the large looking glasses bought from the Comte de Moustier (the other is at the Smithsonian), several of the French armchairs, and the two landscapes (by English painter George Beck).96 Another pair of armchairs is in the collection of the White House. The "Sopha" may be the hairy-paw Philadelphia Chippendale sofa that is now at the Deshler-Morris House in Germantown, Pennsylvania.97

Much of the furniture which Washington had bought to supplement the Government Furniture was offered to the President-elect at cost, but Adams declined to buy it. The pieces that Washington chose not to keep or give away were sold at auction on March 10, 1797.98 Some of the items listed above (especially the mirrors, brackets, and paintings) could have been objects moved to the State Drawing Room expressly for the sale, which was held in the house. Alexander Hamilton commented upon two large paintings of the Hudson River by Englishman William Winstanley which hung in the room.99 Two additional Winstanley paintings hung in the house, but it is not known in what room.100

The third story of the house contained "cross-passages" (probably a hallway going east-west, stairs to the floor above, and back stairs to the floor below), the public business office of the president, and three lodging rooms. (The public business office most likely was the west front room, the largest room on the floor,101 which would have had the same dimensions as the yellow drawing room below it.) Washington had an office staff of three or four secretaries ("the Gentlemen of the family") plus his chief secretary, Tobias Lear, all of whom lodged as well as worked on this floor. Lear and his wife Mary lived in one of the rooms with their son Benjamin, who was born in the house in March 1791. Mrs. Lear was an early victim of the yellow fever epidemic, and died in the house in July 1793. When the son of the Marquis de Lafayette came to live with the Washingtons in April 1796, he probably lodged in one of these rooms.

The attic or garret was even more crowded, with a dozen or more servants living in it. At Lear's suggestion, the two larger chambers (probably those facing the street) were divided to create a pair of additional lodging rooms, making a total of six on the floor. If the initial room assignments were as Lear and Washington anticipated, one room would have been for the steward and his wife (south side), two for the white male servants (one on the south side, one on the north), one for the white female servants not housed over the wash house (north side), one for Mrs. Lear's maid (north side), and the last for the three male enslaved Africans not housed in the addition to the smokehouse (north side).

The original four rooms in this story had been lighted by dormer windows — two facing north and two facing south. The eastern and western walls of the house do not seem to have had windows in their first three stories, but, if there were the usual windows in the gables facing the side yards, each of the six servant rooms could have had a window.

It is not surprising that there is much less known about the backbuildings than the main house, since these were spaces normally not visited by the public. The 1773 insurance survey, the 1785 groundplan, and the 1798 insurance policies generally agree on the dimensions of the individual rooms, but, with the exception of Abigail Adams's description of the second story of the bath house, little documentation has been found on the number and location of the windows and doors.

The kitchen ell was connected to the main house by a piazza. The 1773 insurance survey lists the dimensions of this one-story passage as 7 by 14 feet, possibly with 9-inch brick walls, which would have made the interior width as little as 5 feet 6 inches. (The 1798 insurance policies do not mention the piazza or its dimensions, and by that time it would have been a two-story structure.) It is the writer's conjecture that the piazza was widened when the second story was added to it, and that one story of the back stairs was contained within it.102 These alterations were probably done 1781-82, at the same time that the bath house was built, and it seems probable that the bath house and the rebuilt piazza would have been constructed as a single unit. (In the conjectural floorplans, the piazza has been widened 3 feet over the dimension listed in the 1773 insurance survey. Lear's description of the steward's room lends credence to the piazza having been widened westward.)103

To the east of the piazza was the first story of the bath house, which consisted of a bathingroom and (almost certainly) a hallway. It is likely that the bathingroom was in use during Washington's tenancy (otherwise it would have been an obvious place to house servants, and neither he nor Lear suggests this). In Burt II's 1875 address, he quotes a March 1795 contract between Robert Morris and Andrew Kennedy (the new owner of the property) listing the items in the house of which Morris retained ownership. Included in this were "the marble and wooden baths, with the copper boiler, apparatus of the bath etc."104 — items which may have been used or stored in the bathingroom below the President's study. Among the things that Washington took back to Mount Vernon in 1797 was "one Tin shower bath,"105 but it is not known if this was in use in Philadelphia.

(It has been assumed that the bath house/piazza was constructed with a cellar — the conjectural floorplan shows a cellarway on the north wall, leading to the wood yard. This will be discussed in the second part of this article.)

Even after the items mentioned in the 1795 contract were removed from the house, at least one bathtub must have remained — Abigail Adams wrote her sister in June 1798: "We have began the use of the cold Bath, and I hope it will in some measure compensate for the want of a braceing Air. The largness and hight of our Rooms are a great comfort and the Nights are yet tolerable, and I have freed myself for the season of any more drawing Rooms. Dinners I cannot."106

Morris's well was located to the west of the piazza, in the paved yard, near the northwest corner of the kitchen. It seems logical that the well (and the pump which was inserted into it) would have been covered by some sort of roof (as shown in the plan), and this may have been the section of the kitchen ell which came, according to Lear, "within 5 or 6 feet" of the proposed "Bow window."107 Washington mentions a "small room adjoining the Kitchen (by the Pump),"108 but whether this was some sort of shed attached to the kitchen ell (as shown in the plan between the piazza and the well) or a partitioned area within the ell itself has not been determined. The water supply for the house was stored in cisterns, which may have stood atop the roof of the shed.109

To the south of the piazza was the kitchen ell which was 20 x 55 feet (exterior dimensions), and consisted of a large kitchen, about 18 x 36 feet (interior dimensions), and a washhouse or laundry, about 18 x 16 feet (interior dimensions), behind it. The ovens and cooking facilities must have been extensive, since there was generally formal entertaining several times a week, including State dinners on Thursday afternoons at four o'clock, often with thirty or more guests.

Sometime after 1773, a second story was added to the kitchen ell (most likely by Robert Morris in 1781-82). Two bedrooms (probably the Morrises' own bedroom and a nursery) were carved out of the space above the kitchen. Sheltered from the street, with the walled garden on one side and the paved yard on the other, these rooms must have been both comfortable and quiet. If equal in size, each room would have been about 18 feet square.

Washington and his wife raised two of her grandchildren, Nelly and George Washington Parke Custis, who were eleven and nine in 1790 when the family moved to Philadelphia. The president took one room (most likely the rear one) over the kitchen for himself and Mrs. Washington, and had the other divided into two bedrooms for the children. His plan was that the two female enslaved Africans in the household would sleep in these rooms with the children. The laundresses (and probably the kitchen maids) were to sleep in the room over the washhouse.

Some of the furniture preserved in the Washingtons' bedroom at Mount Vernon was used by them in the bedroom in Philadelphia. The famous bed in which Washington later died was in this room. The writing desk from the Comte de Moustier, a dressing table mirror, and an easy chair also may have been here.

In addition to building the servants' hall, Washington made several changes to the backbuildings before moving into the house. The smokehouse adjoining the south wall of the wash house was to be converted into a lodging room, probably for the white coachman. A second room was ordered built between the smokehouse and the cow house for the three male enslaved Africans who worked in the stable. The President brought fourteen horses to Philadelphia from Mount Vernon. Ten of these were accommodated in the brick stable and (wooden?) stable, the cow house was converted into two additional stalls, and the last pair of horses were boarded with Hiltzheimer (the diarist), who ran a livery stable a block away.

Washington's presidential household had four vehicles — the grand, white, Coach of State for ceremonial occasions (which sat four, and was pulled by six horses), a phaeton or open carriage, a cream-colored chariot or light coach (which probably also sat four), and a work or baggage wagon — all of which, apparently, could fit in the coach house.110 Chickens seem to have been occasionally raised on the premises, and were probably kept in the stable yard.111 Household pets included Mrs. Washington's parrot and Nelly Custis's dog "Frisk."112

The President's House was one of the largest houses in Philadelphia (by 1787 the Bingham Mansion was larger), but with thirty or more people living in it, it must have been crowded.113 Washington received a salary of $25,000, seemingly an enormous sum in the 1790s, although out of this he was required to pay the rent and all of the expenses associated with the house, pay the salaries of his household and office staffs, feed and clothe his family and enslaved Africans, and — most expensive of all — provide all of the food and drink for the State dinners and the numerous other public entertainments. Not surprisingly, in most of the years he was president, Washington outspent his salary.114

The second part of this article will chronicle the misinformation about the size, location and physical appearance of the President's House, and how confusion over the building led to the demolition of its remaining walls in the mid-twentieth century. The cover of this magazine shows a conjectural elevation of the house. The evidence upon which it is based will be presented, along with an estimate of how much of the buildings may remain under Independence Mall.