George Washington: The Soldier Through the French and Indian War

Page 2

In February, 1755, General Edward Braddock arrived in Virginia at the head of 2,000 British troops. He was a gallant officer of distinguished record, but inexperienced with warfare in the American terrain and the techniques employed by the French's native allies. Having heard of Washington's deeds and talents, the general invited the young lieutenant-colonel to serve with him. In a letter addressed to Robert Orme, General Braddock's aid-de-camp, dated March 15, 1755, Washington responded with enthusiasm and more than a little flattery:

"It is true, Sir, that I have, ever since I declined my late command, expressed an inclination to serve the ensuing campaign as a volunteer; and this inclination is not a little increased, since it is likely to be conducted by a gentleman of the General's experience. but, besides this, and the laudable desire I may have to serve, with my best abilities, my King and country, I must be ingenuous enough to confess, that I am not a little biassed by selfish considerations. To explain, Sir, I wish earnestly to attain some knowledge in the military profession, and, believing a more favorable opportunity cannot offer, than to serve under a gentleman of General Braddock's abilities and experience, it does, as may be reasonably suppose, not a little contribute to influence my choice."

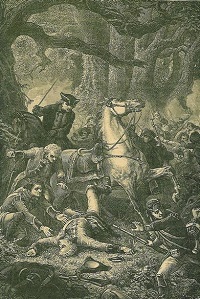

Braddock and his troops were seasoned and highly trained soldiers, but their experience was almost exclusively on the open battlefields of Europe, in stark contrast to the forests of America. Recognizing the importance of familiarity with the terrain, both the French and English had attempted to recruit local native tribes to their side, but the French had had a head start and had considerably more native allies. These factors led to the incident for which General Braddock is chiefly remembered today: The disastrous Battle of the Monongahela.

General Braddock hoped to recapture Fort Duquesne, and began a march toward the fort along with two regiments of soldiers and heavy cannons for the upcoming siege. But Braddock and his troops never had the opportunity to attack the fort. The French, alerted by native scouts to the massive movement of British troops, met Braddock's forces about ten miles south of Fort Duquesne, just after they had crossed the Monongahela River, on July 9, 1755.

Washington described the disastrous defeat in a letter to Governor Dinwiddie dated July 18, 1755:

"We continue our March from Fort Cumberland to Frazier's (which is within 7 miles of Duquesne) without meeting any extraordinary event, having only a straggler or two picked up by the French Indians. When we came to this place, we were attacked (very unexpectedly) by about three hundred French and Indians. Our numbers consisted of about thirteen hundred well armed men, chiefly Regulars, who were immediately struck with such an inconceivable panick, that nothing byt confusion and disobedience of orders prevailed among them. The officers, in general, behaved with incomparable bravery, for which they greatly suffered, there being near 600 killed and wounded--a large proportion, out of the number we had! The Virginia companies behaved like men and died like soldiers; for I believe out of three companies that were on the ground that day scarce thirty were left alive. Capt. Payroney and all his officers, down to a corporal, were killed; Capt. Polson had almost as hard a fate, for only one of his escaped. In short, the dastardly behaviour of the Regular troops (so-called) exposed those who were inclined to do their duty to almost certain death; and, at length, in spite of every effort to the contrary, broke and ran as sheep before hounds, leaving the artillery, ammunition, provisions, baggage, and in short, everything a prey to the enemy. And when we endeavoured to rally them, in hopes of regaining the ground and what we had left upon it, it was with as little success as if we had attempted to have stopped the wild bears of the mountains, or rivulets with our feet; for they would break by, in despite of every effort that could be made to prevent it."

In a letter to Robert Jackson, dated August 2, 1755 George Washington expressed his utter disgust at the debacle, so contrary to the valor and record of the British Regular troops. He wrote:

"It is true, we have been beaten, shamefully beaten, by a handful of men, who only intended to molest and disturb our march. Victory was their smallest expectation. . . had I not been witness to the fact on that fatal day, I should scarce have given credit to it even now."