Oney Judge

More is known about Oney Judge than any other Mount Vernon slave because she lived to an old age, and she was interviewed by abolitionist newspapers in the nineteenth century.

Oney (born c. 1773) was a dower slave, the daughter of Betty, a seamstress, and Andrew Judge, a white English tailor who was an indentured servant at Mount Vernon in the early 1770s. Austin, about fifteen years Oney's senior, would have been her half-brother. Washington does not seem to have recognized Oney as being Judge's child, which may indicate that Judge himself did not admit paternity.

At about age ten, Oney was brought in to the manor house, possibly as a playmate for Mrs. Washington's granddaughter Nelly Custis. Oney became an expert at needlework, and eventually became Mrs. Washington's body servant. In April 1789, Oney was one of seven enslaved Africans brought to New York City by the Washingtons to work in the presidential residence. With the change in the capital in November 1790, she was brought to Philadelphia, and probably shared a room with Nelly in the President's House.

Oney is recorded as accompanying Mrs. Washington on shopping trips and social visits. There are entries in the household ledgerbooks for clothes for the teen-aged girl and trips to the circus. Philadelphia was a center of abolitionism, and had a large free black population. Oney made friends among the free blacks.

Washington recognized that slavery was unpopular in Philadelphia, and began to replace the slaves in the presidential household with white German indentured servants. Austin died in December, 1794, on a trip back to Mount Vernon. This left Oney, Moll and Hercules.

Mrs. Washington's eldest granddaughter, Elizabeth Custis, married English expatriate Thomas Law on March 20, 1796. Washington invited the couple to visit Philadelphia and stay at the President's House. Mrs. Washington informed Oney that she was to be given as a gift to the bride.

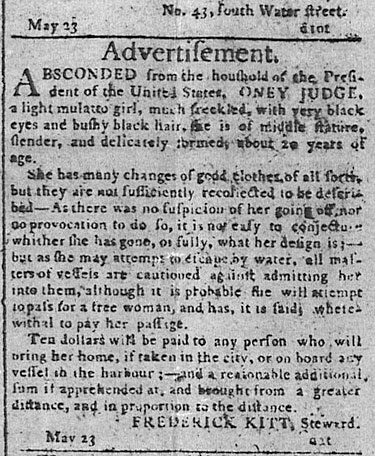

Oney planned her escape with the aid of her free black friends. She slipped away one night in late May 1796 while the Washingtons were having dinner, and was hidden by her friends until she could find passage on a northbound ship. Oney either went directly to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, or arrived there by way of New York City.

Back in Philadelphia, Mrs. Washington felt betrayed, and claimed that Oney must have been abducted and seduced by a Frenchman. She wrote that Oney had always been well-treated, and even had a room of her own (Nelly was attending finishing school in Annapolis). The First Lady urged the President to advertise a reward for Oney's recapture, but Washington refused, realizing how unpopular that would be.

Later that summer, Elizabeth Langdon, daughter of Senator John Langdon of New Hampshire, spotted Oney walking on a street in Portsmouth. Elizabeth was one of Nelly's closest friends, a frequent visitor to the President's House, and (reportedly) a classmate at the same Annapolis finishing school. Oney avoided Nelly's friend, but either Elizabeth or her father wrote to Washington telling him where Oney could be found.

Washington asked Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott to handle the matter, and the latter wrote to Joseph Whipple, the Collector of Customs of Portsmouth, requesting his help in the return of the President's wife's property. Whipple made an attempt at complying with what must have seemed like an intimidating order, but warned in a letter that abducting the girl and placing her on a ship headed south might cause a riot on the docks. Whipple interrogated Oney, and reported to Wolcott that, "After a cautious examination it appeared to me that she had not been decoyed away [by a Frenchman] as had been apprehended, but that a thirst for compleat freedom which she was informed would take place on her arrival here & Boston had been her only motive for absconding."

Scared, lonely and miserable, Oney tried to negotiate through Whipple. She offered to return to the Washingtons, but only if she would be guaranteed freedom upon their deaths. An indignant President responded in person to Whipple's letter: "To enter into such a compromise with her, as she suggested to you, is totally inadmissable [sic], … it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference [of freedom]; and thereby discontent before hand the minds of all her fellow-servants who by their steady attachments are far more deserving than herself of favor."

Two years later, Washington's nephew, Burnwell Bassett, Jr., traveled to New Hampshire on business. He was entertained by the Langdons, and, over dinner, mentioned that one of the things he hoped to accomplish during the trip was the recapture of Oney. This time the Langdons helped Oney, who was now married to a sailor named Jack Staines, and the mother of a child. Word was sent to her for her family to immediately go into hiding. Bassett returned to Virginia without Oney.

Oney had three children with Staines, all of whom predeceased her, as did her husband. Because of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 which Washington signed into law in Philadelphia (probably in his private office barely a dozen feet from where Oney slept), she lived the rest of her life as a fugitive. Ona Judge Staines died in Greenland, New Hampshire on February 25, 1848.

Two 1840s Articles on Oney Judge