Temple's Diary

A Tale of Benjamin Franklin's Family

In the Days Leading up to The American Revolution

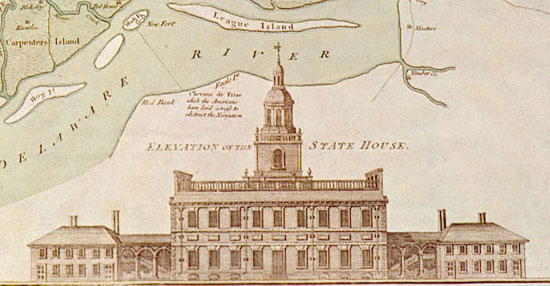

The Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) in 1777

This is the big day, the day the second Continental Congress is to assemble in Philadelphia. They will meet at the Pennsylvania State House this time, where the legislative Assembly of the province convenes.

The building has a large, majestic chamber in which the congressional sessions will take place. Now that the Americans are not afraid to speak out publicly against the British, they feel confident enough to hold their meeting at the more spacious State House, which is British property, after all, instead of the more cramped Carpenters' Hall.

I learned yesterday that Philadelphia is the third-largest English-speaking city in the world after London and Edinburgh. And I had believed it to be some sleepy village! Its population is around 40,000 — with some surrounding districts taken into account. Still, it is no match for London. It has no theater, no concert hall, no ballet, not many of the pleasures of life.

We had a very early breakfast which gave Grandfather the time to ask Uncle Richard a few questions. He is particularly interested in the non-importation agreement that concluded the first Continental Congress. The desire for self-sufficiency is a powerful drive in Grandfather. Woe to those who disagree with him. "I don't need you. See if I care," is what the other party is likely to hear when speaking with the resolute old man.

I remember the relish with which he told me that at the time of the Stamp Act — the first of those Acts that would bring the colonists so much discontent — he had informed the House of Commons in London that America could do without English tea, without English wool, without English anything. He knew how much the British merchants counted on the American market and was certain that they would put pressure on their government to abolish the hated tax. It worked then, in 1765. I'm not sure, though, that it would work today.

Anyway, Grandfather wanted Uncle Richard to tell him how far Pennsylvania had gone on the road to economic self-sufficiency. "Well," announced Richard, "a steelworks has started in town and they produce good tools."

— "Is that the only local business?"

— "Well, to increase the output of wool, no sheep under four years old can be slaughtered anymore, and the butchers have agreed not to sell lambs coming from Britain until October, to encourage domestic production."

— "Anything else being encouraged?"

— "Yes. The cultivation of flax and hemp, the manufacture of gunpowder, woolen goods, nails, wire, steel, glass, copper in sheets, tin plates, malt liquors, paper made from rags, all of these activities are encouraged, notably by your brainchild, the American Philosophical Society." (Oh yes, another of Grandfather's grand ideas, when he brought together the best brains in town and beyond to cooperate on clever schemes and write scholarly papers, making Philadelphia, I'm told, the intellectual center of America.)

Still, all of those homegrown efforts must have seemed inadequate to our Dr. Franklin. He shrugged his shoulders sadly as he left the table and prepared to march in his freshly pressed suit with the other delegates.

Uncle Richard (Richard Bache)

"Let's hurry, Temple," says Uncle Richard, as soon as Grandfather leaves the room. "We want to be near the front of the crowd when the delegates arrive."

I like to be called Temple — I think it's more manly than Billy. And I like my uncle's accent, still so English. His accent is from the north of England. In school we used to make fun of a Yorkshire boy who had a similar twang, but now I rejoice to hear it. And then, like me, Uncle Richard sometimes says "we" when he means the British and "they" for the colonists, but he quickly catches himself and I have to repress a smile.

All this encourages me to ask him suddenly, as we are walking along, "Uncle Richard, which side are you on, deep in your heart?" He stops short and looks at me, pained and puzzled. Slowly he says:

— "That awful question. My mother and sisters, you know, still live in England. My brother who emigrated a little before me and is now a merchant in New York, is an ardent loyalist. As for me, since I entered the Franklin family, I am for the patriots, as the discontented colonists call themselves, but I hope they won't push too, too far. Your grandfather is the most intelligent man I have ever met, and also the most clear-sighted. I am deeply impressed by his fervor and I feel I should follow his lead. To tell you the truth, Temple, I am also somewhat in awe of him ..."

— "I noticed he calls you Son. Doesn't that mean he is fond of you?"

— "That was not always the case. He was extremely upset when Sally and I decided to marry. You might even say that we were married against his will."

— "How can anybody do something against his will?"

— "Well, we did. Do you want to hear the story?"

— "Of course!"

— "I was engaged to a lovely girl called Peggy Ross who was Sally's closest friend. When Peggy fell dangerously ill, I often met Sally at her bedside. When nothing could save Peggy we were both grief- stricken. We turned to each other for comfort, and gradually developed an intense affection that led me to proposing marriage. Sally's father had been in England for years by that time, and left the decision to his wife. Deborah's happiness was to see her daughter happy and she quickly consented. Unfortunately, William, as Sally's older brother, felt that he had to look into my financial situation, and what he discovered was not to his satisfaction. He related to Dr. Franklin that in his opinion I was a mere fortune hunter."

"Your grandfather promptly let us know that marriage was out of the question. Sally fell into such despair that Deborah decided, for the first time in her life, to defy her husband's wishes. The wedding took place on a beautiful October day, with all the ships in Philadelphia's harbor flying their flags in our honor. What a sight that was!"

We had been walking fast and Uncle Richard stopped to catch his breath.

— "For more than a year Dr. Franklin never so much as mentioned Sally in his letters. We named our baby Benjamin Franklin Bache in the hope of pleasing him, but it did not help. Sally must have been the most tearful young wife ever."

I tried to imagine Aunt Sally crying so much, but I couldn't.

— "Only when I went over to England to visit my family in 1771, did I meet Dr. Franklin. His attitude began to soften, and he even lent me some money for a new start in business — along with giving me prudent advice."

I don't know how successful Uncle Richard has been in his new business, but now that Grandfather is back in Philadelphia, Richard certainly tries hard to please him. Grandfather is captivated by the antics of Benny and Willy. That man is surely enchanted by children. Willy-the-Bold is the one who enchants him the most, I'd say. Grandfather compares Willy to Hercules who, while still in his crib as the legend has it, strangled two serpents sent to kill him. I think he sees the American colonies in Willy, getting ready to defy the mighty British Empire one day. When it comes to Benny, Grandfather tries to teach him things. Benny is a serious little boy, anxious to please the grown-ups.

We're in front of the State House now, ready for the spectacle. And what a spectacle!

"High Street, from Ninth Street" by William Birch.

"High Street, from Ninth Street" by William Birch.The City Cavalry of Philadelphia, all two-hundred of them, rode six miles out of town to greet the distinguished guests and escort them to meet the excited crowd. The delegates arrive in all different types of carriages. In the first carriage, an open one, ride two of them, one short and plump, the other tall and thin. Uncle Richard whispers that the short one is Sam Adams, the famous radical from Boston whose followers call themselves the Sons of Liberty — a noisy group — and the other is John Hancock, the richest merchant in New England. He does look full of himself. Those two are the men aroused by Paul Revere during his midnight ride. In the second carriage, my uncle points out John Adams, a distinguished lawyer in Boston and one of the leaders of the patriots. This Adams, who looks deep in thought, is the second cousin of that troublemaker Sam Adams.

And so it goes. Dozens of carriages rolling along while all the bells in the city ring out, drums and fifes sing their song, and the crowd cheers its favorites — Grandfather, I think, more than anybody else. As always, I am torn between two emotions: pride in being the grandson of such an admired character, and panic when I wonder what on earth is expected from me now that the family reminds me three times a day that I am a Franklin.

Soon after Grandfather goes past, there appears a tall, very tall man in uniform, a man who truly cuts a fine figure and elicits even more thunderous cheers than Dr. Franklin — especially high-pitched huzzahs from the women. I feel almost offended.

— "And who could he be?" I ask Uncle Richard.

"A rich Virginian," he tells me, "by the name of George Washington. He owns large plantations down there, and was also a land surveyor who bought up much property. Plus, as you see, he is an officer, a veteran of the French and Indian War. And do you have any idea how he came to be so wealthy, Temple? He married the richest widow in the county. Keep that in mind my boy."

As if a rich widow would marry me!

After an announcement that all Congressional deliberations will be kept secret, the doors of the State House are closed, the crowd disperses, and we have a chance to look at the building. It is truly impressive. Glowing red bricks, a façade that must be at least a hundred feet long with arcades on each side leading to smaller wings, and beyond the wings a little shed on the left and the right. A staircase and belfry, and a large bell. In the center, a cupola that I like and shall draw some day. (Perhaps I'll be a master builder like those fellows from Carpenters' Hall.)

This edifice, where they have been conducting the affairs of the province for the last 40 years, would not look out of place in London. It has majesty, and will likely acquire still more by the time the Americans start counting in centuries, as we English do, and not in years.

But that is not their fault. William Penn arrived here less than a century ago — in 1682 I think — and what did he find? A forest. Penn-sylvania, Penn's forest. Maybe that's why so many streets bear the names of trees?