Philadelphia Merchant's Exchange

Philadelphia's Merchants Moved from Coffee House to Tavern to This "Temple of Commerce"

In Philadelphia's formative years, it was neither bohemians nor slackers who congregated in the city's coffee houses. Rather, it was the members of the business and maritime communities who gathered at places like the London Coffee House to cut deals, attend auctions, talk politics, read newspapers, or grab a light meal, called an "ordinary."

Opened a few years after the Liberty Bell was forged, The London Coffee House was situated at the once busy corner of Front and High Streets hard on the city's docks. Here schooner-owners would advertise their inventory of goods over schooners of ale. Lots of lots of real estate were offered over pots and pots of coffee. This establishment was also the venue for vendues — public auctions of sundry merchandise.

Adding to the animated scene was a twice-weekly market selling grains and meats from the hinterlands. It was operated out of sheds on High Street across from the coffee house. at high noon on market days monetary showdowns would occur when rivals tried to outbid each other during a large horse auction.

THE CITY TAVERN

By the early 1770s, the London Coffee House could no longer cater to the business demands of the swelling city. Recognizing the need for larger quarters, several nabobs of the social and mercantile aristocracy built the Merchant's Coffee House which came to be better known as the City Tavern. A business card distributed by an innkeeper at City Tavern in 1789 read, "Opened and established by the subscription of Merchants, Captains of Vessels, and other Gentlemen, at the CITY-TAVERN, in Second-street. The two Front Rooms of the house are especially appropriated to there [sic] purposes... CHANGE HOURS from 12 to 2 at Noon, and 6 to 8 in the Evening." The card went on to advertise rooms for rent, a restaurant, a stable, and liquors, at "reasonable rates."

Not only did the Tavern serve as the hub of the business community for about a half a century, it also played host to members of the First Continental Congress and such luminaries as Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Lafayette and John Adams — he called it "The most genteel tavern in the country."

THE MERCHANT'S EXCHANGE

During Andrew Jackson's first tenure in office, Philadelphia — along with the rest of the nation — was in the midst of an economic boom. Transportation advances in the forms of canals and better roads opened up the West for economic exploitation. A generation of industrialists came to the fore. Businesses were born to meet the needs of a burgeoning population, augmented by large numbers of immigrants. The growing community necessitated a new center for business.

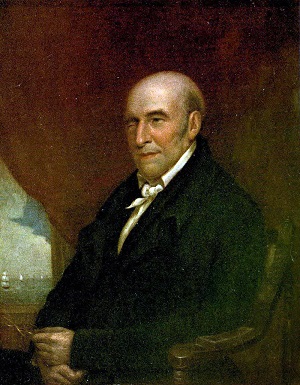

Steven Girard

JR Lambdin, pre-1918

In 1831, a new group representing the social and business aristocracy organized into a society for building an Exchange. Included in the group of trustees for the new enterprise was Stephen Girard arguably the wealthiest man in the nation. After the charter for the First Bank of the United States lapsed, Girard bought the building and established a bank named for himself in its quarters. Not surprisingly, then, the site chosen for the new Exchange was within eyesight of Girard's bank.

To design the Exchange, the directors chose a rising local architect, William Strickland. Strickland was the architect of the steeple on Independence Hall, the U.S. Naval Asylum, and the U.S. Mint. He had also just submitted a much-admired blueprint for the Second Bank of the United States which he would later build.

THE STRUCTURE

The building can be seen as two distinct and handsome structures. On the Third Street side, the rectangular main structure mirrors the 1830s American's fascination with Greek architecture. The august Corinthian portico with four columns and two pediments stands on top of a heavy basement level featuring four stout columns with capitals which look like corn husks. If the Greeks had a god of money — this could be home.

Yet, it's the semi-circular portico, an ingenious adaptation for an odd-shaped lot, that makes the Philadelphia Merchant's Exchange truly memorable. Dock Creek, a turgid and polluted inlet of the Delaware River, once flowed along what is now Dock Street on the building's north side. After the creek was paved over, the city of William Penn's uniform grids had one of its few curved streets. On the basement level, the Exchange's curve follows the outline of Dock Creek and melds into it. From the second story rise six Corinthian columns. Sets of stairs, watched over by recumbent lions (sculpted by Signor Fiorelli of Philadelphia, a gift from a local merchant in 1838), run up from both sides of the basement level and lead to tall doors. Long, svelte windows give way to rectangular blank inserts under the portico. The lip of the portico is decorated by shells of Minoan design.

An 1831 local newspaper piece declared, "Philadelphia is truly the Athens of America." How apropos then, that Strickland based the Exchange's tower on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. Ships could be seen approaching up and down the river, if viewed from the tower.

After Strickland finished the Exchange, the city gained what one architectural critic called an "audacious building, looking out from its sweeping curve with such graceful bravery as gives a veritable Victory of Samothrace air."

THE INTERIOR

The Exchange Room in the curved section of the building was remarkable. It had a mosaic floor, domed ceiling supported on marble columns, and frescoes on the walls and ceiling. The fresco painter was Nicola Monachesi who had executed frescoes in many of Philadelphia's Roman Catholic churches.

Real-estate dealing, auctions, and business transactions of all kinds took place in this room, where shipping reports and both local and from all over the world were posted.

Inside the building was a post office. further, many marine insurance companies with names like the Delaware No. 3 had offices in the building. Architect Strickland retained an office for himself at the Exchange. Naturally some space was given over to a coffee shop.

EXCHANGING THE EXCHANGE

By the Civil War businesses had begun to move toward the western part of the city. Eventually, Broad Street would became Philadelphia's new financial and political center. Hence, the first Exchange was dissolved in favor of the Corn Exchange in 1866. By 1875 the Philadelphia Stock Exchange took the place of the Corn Exchange. Though offices were still leased in the Merchant's Exchange, its interior gradually fell into disrepair. In 1900, the Stock Exchange moved back to the structure for a time, but the building started down a steep slope of decline. In 1922 it was sold to a firm that made it a Produce Exchange. An open-air market surrounded the Exchange. Vendors hawked vegetables from pushcarts. A gas station was built on the Dock Street side.

Photographs of the era show the magnificent building surronded by rickety sheds and trucks from the Garden State, across the river.

In 1952, the Independence National Historical Park bought the structure and maintains offices here to this day.

At the Exchange's dedication speech in 1832, Solicitor John Kane looked 150 years into the future and remarked, "the building which we have founded shall stand among the relics of antiquities, another memorial to posterity of the skill of its architect — and proof of the liberal spirit, and cultivated taste, which, in our days, distinguish the mercantile community."

He was right.

- The cornerstone was laid on the 100th anniversary of Washington's birth.

- Over one million bricks were used in constructing the Exchange.

- Architect Strickland designed the steeple on Independence Hall as well as the Tennessee State Capitol in Nashville — which he is buried under.

- The tower is based on an adaptation of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens.

- Location: South 3rd at Walnut and Dock Streets (Map)

- Built: 1832-34

- Commissioned by: Financiers and merchants

- Original Architect: William Strickland

- Original Marble Mason: John Struthers

- Style: Greek Revival

- Cost to build: Land, $75,000; Construction $159,435

- Tourism information: It is now offices for the Park Service, with a small public exhibition space open to the public.