Franklin and the Vexing Question of Race in America

by Dr. Emma Lapsansky-Werner, Haverford College

Emeritus Professor of History

Emeritus Curator of the Quaker Collection.

Benjamin Franklin: probably no American child over the age of 10 doesn't recognize his name. We all know he was an American hero from "some time in the past," and in 2005, several museums around the world celebrated his life in an exhibition titled Benjamin Franklin: In Search of a Better World. In 2018, the legendary Franklin would have celebrated his 312th birthday. Of what use is such an old legend? What can Franklin—a slaveholder-turned-abolitionist—teach us today?

Franklin correspondence and bifocals on display

From an exhibition at the Franklin Institute

The only one of the Founding Fathers to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Paris, and the Constitution, the long-lived Franklin was multifaceted: innovator, philosopher, entrepreneur, statesman, public intellectual, and—at the end of his life—an anti-slavery advocate. A man ahead-of-his-times, his limitless ingenuity fueled a seemingly limitless spectrum of "modernizations:" the concept of a lightning rod; improvements to the wood-burning stove; the magic of bi-focal glasses. Franklin was among the first to advocate the "time-driven" workday, focused around laboring for a preset period of time, as opposed to the "task-driven" workday, which allowed a worker to quit whenever assigned jobs were completed.

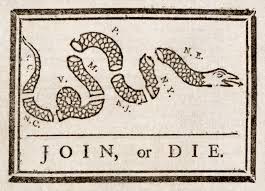

And surely, part of Franklin's enduring legacies result from his commitment to "democracy" and "community," including helping to conceive a postal service, a lending library, a hospital for the poor, a fellowship for "promoting useful knowledge," a university, and a widely-publicized cartoon urging the squabbling American colonies to "join or die."

But the publisher/inventor/writer was also a man of his times, struggling to grasp how past notions of "community" should inform the "community" of the future. One vexing aspect of the community-of-the-future was defining the role and rights of "Others" in the new society: women, immigrants, Native Americans, and—especially—African Americans and/or slaves. Such issues bedeviled Franklin and his fellow Constitution-framers.

In many facets of his life and work Franklin—himself a slaveholder—repeatedly bumped up against the conundrum of race, and like most men of his age and status, he lacked templates for shaping answers. But unlike many of his peers, the pragmatic Franklin wrestled with the vexing questions, often reaching ambiguous—even contradictory—answers.

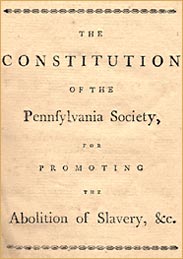

In the last decade of his life, Franklin served as president of an abolition organization, but his progress to that role is murky and inconsistent. As of the 1750s, he showed himself to be suspicious of many "Others:" disparaging "low women," Catholics, and Jews; decrying "alien" German immigrants who would "swarm into our settlements;" and labeling Native Americans as "drunken "savages who delight in war. take pride in murder," and should be pursued with "large, strong, and fierce dogs." Yet, in the 1760s, when white Americans attacked an Indian settlement, he labeled the attack "white savagery." African Americans, he described as "sullen, malicious, revengeful" and "by nature [thieves.]" Yet, ever the inquiring scientist, he visited a school for black children, emerging from the visit with a "higher opinion of the black race than I had ever before entertained," and conceding that slaves' tendency to thievery might be attributed more to their situation than to "nature." But he framed his concern for "poor Negro slaves who are . . . sick or lame" only in the context of the burden they placed upon their owners. Late in his life, he ordered that his slaves should be freed — partly out of his concern that slaves and servants made their owners lazy and unambitious. But for all this inconsistency of thought, Franklin consistently showed himself to be thoughtful, open, teachable.

Franklin scholar Lorraine Pangle described Franklin as "the founder who has the most to teach us today, both about the art of living and about restoring civility to our public sphere." Indeed, Franklin consistently kept his eye on what he believed were the loftiest goals of justice and integrity. But Franklin was a man of his times, and some of the context of his times may seem ill-informed and convoluted in today's times. Though modern Americans are often suspicious of "heroes," Franklin can remind us that though "heroes" can be inconsistent and imperfect, they can inspire us toward the possibility of reaching for our own "better selves," even if—in Robert Browning's words—"our reach exceeds our grasp." Always "In Search of a Better World," Franklin was enigmatic, but he was a man of inquiring intellect, broad vision, and a dogged commitment to "justice," "democracy," and "community"—as best he could probe and understand these elusive principles. Indeed, his life and his struggles have much to inform modern America's pursuit of these same elusive principles.

Written for the 2018 Celebration! of Benjamin Franklin, Founder event:

Race Awareness in America