Washington Square

"The everlasting lure of round-the-corner, how fascinating it is." -Christopher Morley

Christopher Morley, a nonpareil perambulator, and a writer who could turn a phrase with the athleticism and grace of a figure skater hitting a triple axel, wrote the following in a 1918 essay entitled Sauntering: "I love to annotate the phenomena of the city. I can be as solitary in a city street as ever Thoreau was in Walden. And no Walden sky was ever more blue than the roof of Washington square this morning."

Morley once lived on Washington Square, in a house facing the great green common, which in later years became "The Christopher Morley Inn." Philadelphia's Washington Square has long been home to a thriving publishing industry and was indeed home to America's oldest publishing house. It's apropos, therefore, that one of the great — as-yet-unrediscovered — American authors lived on the Square.

The periphery of Washington Square consists of 20th-century multi-story apartment buildings, 19th-century townhouses, an Athenaeum with a Victorian bent (another stop along our "virtual" tour), and several businesses, some dating to the 18th century when Washington was President in the then capital city of Philadelphia, and the Square had not yet been named in his honor.

A History of the Square

Washington Square was one of Philadelphia's five original squares as laid out in 1682 by William Penn's surveyor, Thomas Holme. It was then called Southeast Square, as Quakers did not believe in naming places after people. Within 25 years of Penn's arrival, however, the square was being used as a potter's field and a burial yard for strangers in the city. it served in this capacity from 1704 to 1794, a period roughly (and curiously) paralleling the dates of Benjamin Franklin's tenure on earth (1706-1790). Burials were generally done on the cheap: bodies bound in canvas — sans coffins.

For a cemetery, the Square was remarkably filled with life, however. Historian John Fanning Watson in his 1830 "Annals of Philadelphia" writes of two fish-filled creeks that flowed through the Square in the 1740s in addition to a pond that attracted wanton boys. "A creek once ran thru the Square and the aged Hayfield Conygnam, Esq., when he was young, caught a fish of six inches in length. Another aged person told me of his often walking up the brook, barefooted, in the water, and catching crayfish." (Today the only water in the park is found in a fountain in the park's center and in a horse watering trough when rainfall backs up.)

Rites similar to the Mexican "Day of the Dead" celebration were held in the park's early years by the black community. Watson writes, "An aged lady, Mrs. H.S., had told me that she has often seen Guinea natives, in the days of her youth, going to the grave of their friends early in the morning, and there leaving them victuals and rum!"

In the years preceding the Revolutionary War, the Square was deemed a good pasture field — despite (or because of) nearly 60 years of burials! In 1766, Jasper Carpenter leased the field from the city toward that end. Erelong, Carpenter's cows would have to make way for the corpses of American and British soldiers.

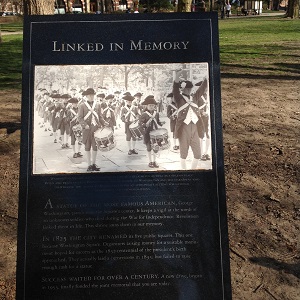

Beginning in 1776, fallen troops from Washington's Army were buried in the Square. Pits 20 feet by 30 feet in length were dug along 7th and Walnut Streets which were then filled by coffins piled one atop another until space in the mass grave ran out. Long trenches the width of the Square were hastily dug on the Square's south side — a permanent barracks for the martyrs of the War of Independence.

John Adams wrote a sad letter filled with lamentation to his wife Abigail on April 13, 1777. "I have spent an hour, this morning, in the congregation of the dead. I took a walk into the Potters Field, a burying ground...and I never in my whole life was affected with so much melancholy."

When the British occupied Philadelphia in 1777, they used the Walnut Street Jail, which then faced the Square, to hold prisoners of war. Draconian conditions caused death in droves. This story is told on the next stop along this virtual tour, at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

More corpses followed in 1793. Those that spent their last days fighting off the chill haze of Yellow Fever, wound up in shrouds underneath the now pacific park.

After the Square was closed as a cemetery, the situation in the area did not initially improve. Historian Watson described the houses that surrounded the Square in 1805 being as "miserable and deformed a set of huts and sheds as could be well imagined."

Improvement started in the form of a public walk in 1815. A tree-planting program began the next year and the Square to this day wears the fruit of a city plan in which over 60 varieties of trees were sown. A "really admirable city arboretum of rare trees," was how America's first landscape architect, Andrew Jackson Downing, described the Square. Walking on the Square 150 years after this beautification project, the historian John Francis Marion observed, "The trees in Washington Square are older, wider-spreading and taller than those in Independence Square, and the square itself has a more open spacious quality."

The 6.4-acre Southeast Square was renamed Washington Square in 1825 to honor the great general and first President.