The Battle of the Clouds: — Part 5 of 5

The Day of the Battle: September 16, 1777

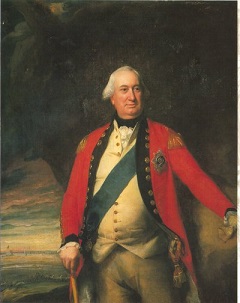

The Marquess Cornwallis

John Singleton Copley,

The troops under Cornwallis set out at midnight but the going was slow. A British officer recorded in his journal that there was "frequent halting on account of the night being very dark." Cornwallis' column was headed toward White Horse Tavern.

Knyphausen's column set out at dawn. Accompanied by General Howe, this column went up the Wilmington Pike toward the Boot Tavern. At Turk's Head, Howe splintered off another column. This column consisted of the Guards Brigade under Captain Matthew. It marched along the Pottstown Pike toward the Indian King Tavern. All three British columns were bellying up to bars.

Around 9 A.M., Washington learned of Howe's advance. Hoping perhaps to catch the enemy unprepared and strung out along their marching paths, he ordered his troops forward to meet the British. The Americans marched slightly south and formed a three-mile line that stretched from one bar, the Three Tuns Tavern, westward to another, the Boot Tavern. It seems only fitting that all the action was centered around bars — because the weather was about to pour.

The Battle of the Clouds commenced at about 1 P.M. when Washington ordered Count Casimir Pulaski, the recently appointed "Commander of the Horse" (Cavalry), to scout the British position and delay their advance. Cornwallis espied Pulaski and the 300 militia he was leading and sent the 1st Light Infantry charging at the Americans. The Americans "shamefully fled at the first fire" and delayed the enemy not at all. A dozen American casualties resulted from this encounter, while the British were "without the loss of a man."

The first meaningful encounter came when Generals Wayne and Maxwell, who had been detached forward to observe the enemies movement on the Chester-Dilworth Road, met Knyphausen's column near the Boot Tavern. Scouting ahead of Knyphausen's column were Hessian Jagers under Count Von Donop. These Hessians unexpectedly came upon the force led by Wayne and Maxwell who charged them. One observer recorded that Donop "was almost cut off," from Knyphausen, but extracted himself after skillfully executing some maneuvers to his left. He rejoined Knyphausen.

Grenadiers were sent to reinforce the Jagers. These units formed an advance line against Wayne and Maxwell, who had taken a position "on high ground among some cornfields." The Jagers, taking a page from the popular image of the Americans, were skilled in "irregular fighting." They fought from behind fences and in fields and woods. At the White Horse Tavern, they "had an opportunity to demonstrate to the enemy their superior marksmanship and their skill with the amusettes." After an intense exchange of fire, the Americans fell back into to a dense forest, "leaving behind a number of killed and wounded."

On a high ground just west of the White Horse Tavern, the British formed a line of battle. Washington was forced to withdraw to "a valley of soft wet ground, impassable for artillery." About this time, Matthew's troops pulled up on Knyphausen's left. They were unopposed and had a clear path into the exposed American flank. Washington, seeing he was in for trouble, ordered a withdrawl to higher ground. Now, the armies were set for a reprise of their Brandywine engagement just five days past. But things looked bleak for the Amercians.

And then the sky grew dark, the thunder cracked, and a heavy rain soaked American and British alike Major Bauermeister would later describe the deluge in a letter: "It came down so hard that in a few moments we were drenched and sank in mud up to our calves."

Low clouds rolled through the valley and driving rain obscured the hilltops, hiding the combatants from each other. Powder was soaked; muskets sodden and useless. Tens of thousands of paper cartridges were ruined. General Henry Knox, commander of the American artillery recalled this as "a most terrible stroke to us." Not only could neither side fire a shot, but the British were even unable to make a bayonet charge. The wind and mud prevented it.

Washington retreated across the Schuylkill still keeping his army between the British and the supply cities.

Thus the Battle of the Clouds yielded few casualties. In the words of historian Edward Gifford, Jr., "It was the peace of God."

It was also another missed opportunity for Howe.