The Conway Cabal

Page 2

Some have suggested that Washington was oversensitive to criticism. But gossip, innuendo, and direct criticism flew about the commander in chief like grapeshot. Likely, he was privy to the reports sent from South Carolina Congressman Henry Laurens to his son John, who was an officer on Washington's staff. These letters were full of juicy anti-Washington whisperings floating about Congress. Laurens, who would later be President of Congress, cannily never named these "Actors, accommodators, Candle snuffers, Shifters of scene and Mutes" who impugned Washington.

Then there were annoyances such as the circulation of an anonymous paper entitled, "Thoughts of a Freeman," written by Washington's enemies in Congress. It was critical of Washington's generalship, and particularly critical of the apotheosizing cult that had grown around him: "The people of America have been guilty of making a man their God."

James Lovell, a Massachusetts delegate to Congress, and anti-Washingtonian wrote to Samuel Adams to complain about his fellow delegates, calling them, "privy Councillors to one great Man whom no Citizen shall dare even to talk about, say the Gentleman of the Blade." In other words, Lovell was concerned that various members of congress were unwilling to hear criticism of the General, while the General's defenders within the military were willing to defend his reputation with their swords. Lovell proved prescient as we shall see later.

Conway and the "weak General" letter

In late October 1777 Conway wrote a letter to General Gates which would bring the situation to a boil. It contained the following paragraph:

"Heaven has been determind to save your Country; or a weak General and bad Coucellors would have ruined it."

As to Conway's motivations in writing Gates, only speculation serves. Perhaps he wished a transfer to Gates's army; perhaps it was part of his overall self-promoting public relations campaign; perhaps it was to rouse anti-Washington sentiment.

Washington received word of the letter in a roundabout manner. A Gates aide, General James Wilkinson, was visiting the headquarters of the American officer Lord Stirling. Apparently while drunk, Wilkinson revealed the contents of the letter to a Stirling officer, Major McWilliams, who relayed its contents to Stirling. Stirling, mortified by "such wicked duplicity of conduct" felt obligated to report the letter's contents to Washington. In turn, Washington fired off a brief letter to Conway letting the upstart know that the contents of his letter had been exposed. Conway wrote back immediately saying falsely that he had never called Washington "a weak General." He went on to write that while he considered Washington a "brave man" he also thought that the general had been "influenced by men who were not equal to him in point of experience, knowledge or judgment." Now he had not only disparaged the General, but his staff as well.

On November 14 Conway offered his resignation to Congress. In enumerating reasons for his resignation he cited the rebuff by Washington, but also Congress's failure to promote him, and the promotion of Baron de Kalb who had held a lower rank than Conway in the French army. Congress passed Conway's letter on to the Board of War, whose members included the influential Thomas Mifflin.

Washington's foes promote Conway

While the War Board considered Conway's resignation, political foes of Washington in Congress promoted Conway to the newly formed position of Inspector General, which bore the rank major general. The Inspector General (ironically the post was conceived by Washington after a suggestion by a foreign volunteer) was to devote himself full time to the preparing of a training manual and assembling and implementing a guide to military maneuvers. Conway would work alongside Washington who was now at Valley Forge but would be responsible only to the War Board. To add insult to injury as far as Washington was concerned, Congress had appointed Horatio Gates as President of the Board of War, on November 27, 1777.

Bust portrait of Baron Johann de Kalb

by Charles Wilson Peale

Second Bank Portait Gallery

Independence National Historic Park

War of the Letters

Naturally, when Conway arrived at cold Valley Forge on December 29, Washington gave him the cold shoulder. Inspector General Conway began to shrink before Washington's wrathful eye and icy formality. In one charged exchange of letters, Washington wrote to Conway asking him how he intended to conduct business. Conway wrote back to the effect that if Washington found his service "disagreeable" that "I am very ready to return to France." Washington shot back that while he was very willing to work with Congress and accept their decisions, members of his staff felt slighted by Conway's promotion - particularly in light of how Conway complained after Baron de Kalb's promotion.

Given enough time a loose cannon will shoot himself in the foot. Conway wrote another letter to Washington:

We know but the great Frederick in Europe and the great Washington in this continent. I certainly never was so rash as to pretend to such a prodigious height. By the complexion of your letter and by the reception you have honored me with since my arrival, I perceive that I have not the happiness of being agreeable to your Excellency and that I can expect no support in fulfilling the laborious duty of the Inspector General.

On January 2, 1778, Washington forwarded Conway's diatribe to Congress along with a cover letter. In his letter, Washington confessed personal disdain for Conway but made it clear it never affected the professional manner in which business was conducted nor was the support Conway expected ever withheld.

Placing Blame and Covering Up

Conway had tracked down that it was Wilkinson who revealed the content of his letter to Gates. He reported this to Thomas Mifflin, who chastised Gates for being careless with his letters.

Gates then wrote a letter concurrently to Washington and Congress. In it he asks for assistance in discovering the means by which Washington came in possession of Conway's letter to him. "Those Letters have been Stealingly copied," he wrote. Washington could do "a very important service, by detecting the wretch who may betray me, and capitally injure the very operations," he wrote. This was the first time that Washington discovered that Gates and Conway had been exchanging disparaging correspondence behind his back. Washington wrote back to Gates. In opening he expresses his dismay at Gates having sent the letter to both himself and Congress, questioning the motives, and then responding by doing the same himself, "lest any Member of that Honbl. body, should harbour an unfavourable suspicion of my having practiced some indirect means, to come at the contents of the confidential Letters between you and General Conway." He then revealed the sequence of events and goes on to say that the act rather than being one of betrayal of Gates was intended rather as an act of "Justice." Washington further stated that he had revealed the contents of Conway's letter to no one outside his family except the Marquis de Lafayette and then only upon demand and with the oath of secrecy. Washington stated that he was desirous of "concealing every matter that could, in its consequences give the smallest Interruption to the tranquility of this Army, or afford a gleam of hope to the enemy by dissentions therein."

Fulfulling Lovell's prediction, Gates challenged Wilkinson to a duel. The challenge was not accepted.

Congress Reviews the Matter

The Cabal collapsed on January 19 when Conway and Gates made a trip to Congress sitting at York. They went before Congress to try to clear their names but would not reveal the original "weak general" letter which was the catalyst for the cabal. Lafayette delegated himself spokesman for the French court. He did his utmost to convey the conviction that France regarded Washington as one and the same with the American cause. France could not even conceive of another commander, he implied. Eventually, that would be the French attitude, but only after Lafayette's efforts - especially his year of personal lobbying in France in 1779 - had worked to make it so.

As we have seen other officers remained loyal to Washington throughout the affair, from the brigadier generals protesting Conway's promotion to the colonels writing anti-Wilkinson memorials to Congress.

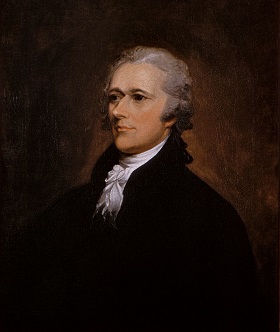

Another staunch ally was aide-de-camp Alexander Hamilton, a master manipulator who wrote a series of letters castigating the plotters.

Congress, in light of the duplicity and foolishness of Gates and Conway, and in possession of letters of support from the majority of Washington's officers was forced to fully support Washington. The movement to unseat Washington lost all steam.

The Fall Out

Thomas Mifflin resigned from the Board of War.

James Wilkinson resigned as Secretary of the Board of War.

Horatio Gates returned to his troops a chastened general.

Portait of Thomas Conway

Unknown artist, 18th century.

Thomas Conway was transferred to a subordinate command in the Hudson Highlands. Naturally he protested this transfer and so resigned from the army. In 1778, Congress accepted his resignation. Yet Conway would not go away. He remained a burr in Washington's saddle by badmouthing the general to anyone who will listen. General John Cadwalader, a staunch Washington supporter, challenged Conway to a July 4 duel, grievously wounding him. Believing his wounds to be fatal Conway wrote a letter of apology to Washington.

After recovering from his wounds, the lucky and still plucky Conway headed back to France. He served as governor of the French colonies in India and then fought against the armies in the French Revolution. Appropriately for someone who had spend his life as a soldier of fortune, he died in exile, in the year 1800