Temple's Diary

A Tale of Benjamin Franklin's Family

In the Days Leading up to The American Revolution

Sometimes, when I cannot fall asleep, I imagine a really happy scene, and it is always more or less the same. I half-dream that we are all together in Aunt Sally's dining room, the whole family eating supper and chatting. Grandfather is at the head of the table, of course, in a jovial mood.

And Father, splendidly turned out as usual, is at his gracious best, sipping the very special French wine he contributed to the occasion. Elizabeth, rustling in one of her exquisite gowns, looks slightly out of place in these ample but somewhat bare surroundings. She smiles, but there is a slight sadness in her face. She makes me think of a princess in exile. But all the others are enjoying themselves, especially Benny and Willy, now and then popping up from under the table. Aunt Sally beams. Uncle Richard attends respectfully to his father-in- law. And me? I am really, finally, totally one of the family, no longer the unknown quantity, the young stranger, the unexpected addition.

The two men in my life are not poles apart this evening, pulling me this way and that. They are reminiscing about their joint adventures, when they were inseparable companions, more like brothers, people used to say, than like father and son.

The key and kite experiment, of course. That is the first to come to mind, that momentous second during a thunderstorm when Grandfather saw the hoped-for spark fly from the kite's string bristling with little hairs to the key held out by William. The decisive proof, at last, that lightning is electricity and not the wrath of God. Today we are all aware that if that storm had been more violent they could have ended up roasted, my future father and grandfather, but they did not know it then. They just hugged and danced in the rain.

What year was it? 1750? 1751? "No, no," exclaims Sally who appears in my daydream, and has the memory of an elephant (just as in real life). "It was 1752! And do you know, Temple, that they could have saved themselves all that trouble and danger if they had learned that the French, one month earlier, had already conducted an experiment that proved your Grandfather's theory?"

Yes, I know, because she has already told me so, but I am beginning to understand that at family gatherings the younger generation is supposed to listen to the stories of their elders as if they had never heard them before, and react each time with the appropriate response. So I say: "What about the French?"

Dalibard's experiment.

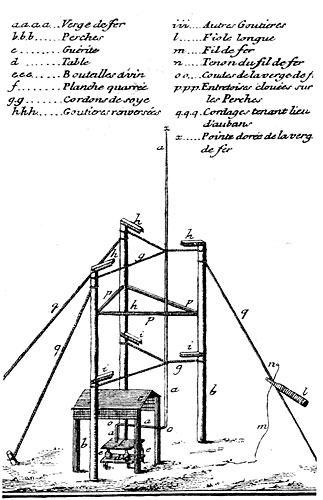

— "Well, a Monsieur Dalibard translated your grandfather's book, Experiments and Observations, into French and, in order to capture the electrical fluid from lightning, he put up an iron rod 40 feet high, with a copper point at its tip, and connected it to a stool placed on a table in a small sentry box. Since he had to return to Paris, this Dalibard entrusted a former dragoon captain with the job of drawing sparks as soon as he heard thunder, by touching the rod with a piece of metal. Well, a storm broke out in May and the brave dragoon quickly sent for the local priest — Catholic, of course, everybody is Catholic in France — who came running. Seeing their priest in such a hurry, his parishioners surmised that the dragoon had been killed and, in spite of a furious hailstorm, they rushed after him. The priest drew abundant sparks, six times within four minutes, he said. On his way home he was met by the vicar and the schoolmaster to whom he related the happening. All of them noticed a strong sulfur smell emanating from his clothes. Something demonic, would you say, Dr. Franklin?"

Dr. Franklin, who loves this episode, is smiling broadly until Sally pushes on: "And now, tell us about the congratulations of the King of France..."

— "Well, Louis XV sent me a medal."

— "Yes, Papa. And tell us in your own words your reaction to that medal."

Grandfather covers his face in mock coyness: "Come on, Sally. Don't be a tease. Get us some pie."

But Sally, in my daydream, is not to be stopped. She turns to me: "Billy, would you believe that in a letter to a friend your Grandpapa compared himself to a little girl who has just received a pair of silk garters? 'They are hidden under her petticoats but she holds her head high because she knows they are there and is proud of them.'"

Everybody laughs while Grandfather pretends to be dreadfully embarrassed.

I generally fall asleep at this point of my reverie but sometimes I imagine one more scene, a scene involving the dimpled girl from the Philadelphia City Tavern. I cannot explain, not even to myself, how she got here, but there she is, helping Aunt Sally to carry the dishes in and out. I join her in the kitchen, she looks up and smiles, and suddenly I put my arms around her and deposit a kiss on each of her dimples. She quickly puts her hands to her cheeks.

— "What are you doing?" I ask.

— "Keeping the kisses warm," she says.

My daydream stops there. I don't know what to say next. Never in my life have I had a conversation with a girl my own age. What does one tell them?

I fall asleep.