The Conway Cabal

In our time George Washington's name is virtually unsullied and unassailable. So it's difficult to comprehend that, like anyone serving in a public capacity for half a century, he had his detractors, especially when things were not going well.

During the dismal autumn of 1777, these detractors included Granny Gates, an American general, a factious Congressional clique, Benjamin Rush, the highly esteemed "Father of American Medicine," and a certain ambitious foreign officer named Thomas Conway. They were all critical of Washington's handling of the war and they all wanted Washington replaced. Whether they united deliberately to form a "cabal," or plot, is debatable; regardless, their sniping, griping, and machinations have come to be known as the "Conway Cabal."

George Washington learned of a letter written by Conway to Gates that called him a weak general; he learned of anti-Washington talk in Congress; and he was aware of broadsides, letters, and talk questioning his abilities. This "cabal" so frustrated and embittered Washington that he indicated that he would resign from the army if his performance continued to be brought into question.

The campaign of 1777 was, by most estimations, the low point of Washington's military career. He retreated from Brandywine and he let slip away a probable triumph in the fog at the Battle of Germantown. Meanwhile his countryman General Horatio Gates had won a smashing victory at Saratoga. There was a desire expressed within the military and within Congress to have the commander in chief sent home to Mount Vernon and to replace him with the more successful Gates.

Among Washington's detractors in Congress were Samuel Adams, Thomas Mifflin, and Richard Henry Lee. This group was dissatisfied with many aspects of the war - ranging from how supplies were procured, to battlefield performance, to the supervision of soldiers by the commander in chief.

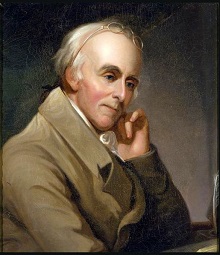

Benjamin Rush

by Charles Wilson Peale

Second Bank Portait Gallery

Indepndence National Historic Park

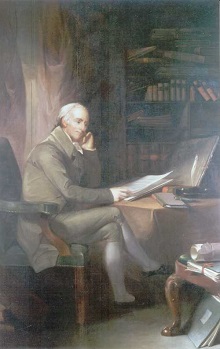

Benjamin Rush

by Thomas Sully

Pine Center Building, University of Pennsylvania Hospital

One of the most vocal critics of Washington's handling of troops was Dr. Benjamin Rush, the Father of American Medicine. This Signer of the Declaration of Independence, though no longer a member of Congress, was a respected army physician. He wrote a scathing, though unsigned letter to Patrick Henry, disparaging Washington's generalship and commending General Gates who was at the head of the northern army. In this letter was the following:

The northern army has shown us what Americans are cable of doing with a GENERAL at their head. The spirit of the southern army is no ways inferior to the spirit of the northern. A Gates, a Lee, or a Conway would in a few weeks render them an irresistible body of men.

In a separate letter Rush wrote, "The present management of our army would depopulate America if men grew among us as speedily & spontaneously as blades of grass."

John Adams, Rush's best friend, echoed the doctor's disgust, "I am sick of Fabian systems in all quarters!"

Thomas Conway's name will forever be linked to the criticism of Washington due to his conspicuous attacks on the General.

After Conway's able performance at the Battle of Brandywine on September 21, 1777, General Sullivan wrote: "His regulations in his Brigade are much better than any in the Army, and his knowledge of military matters far exceeds any officer we have." (It was in rallying Conway's Brigade at Brandywine that the Marquis de Lafayette was wounded in the leg.)

Buoyed by his own bravery at Brandywine, Conway wrote a boastful letter to Congress asking for a promotion to major general. Such a promotion would have hopscotched him over many senior brigade leaders. While he waited for a reply from Congress, Conway continued disparaging Washington. He was overheard saying, "as to his (Washington's) talents for the command of an Army, they were miserable indeed."

When Washington got wind of Conway's self-important letter to Congress, he wrote to Richard Henry Lee protesting any appointment of Conway. "General Conway's merit, then, as an Officer, and his importance in this Army, exist more in his own imagination than in reality: For it is a maxim with him, to leave no service of his own untold, nor to want any thing which is to be obtained by importunity..." Washington goes on to write that promoting Conway would also have a disastrous effect on the morale of his longer-serving, more devoted officers who might resign. Washington continues,

To Sum up the whole, I have been a Slave to the service: I have undergone more than most Men are aware of, to harmonize so many discordant parts, but it will be impossible for me to be of any further service, if such insuperable difficulties are thrown in my way...