40b. Custer's Last Stand

Another Broken Treaty

Gold broke the delicate peace with the Lakota. In 1874, a scientific exploration group led by General George Armstrong Custer discovered the precious metal in the heart of the Black Hills of South Dakota.

When word of the discovery leaked, nothing could stop the masses of prospectors looking to get rich quick, despite the treaty protections that awarded that land to the Lakota. Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, the local Indian leaders, decided to take up arms to defend their dwindling land supply.

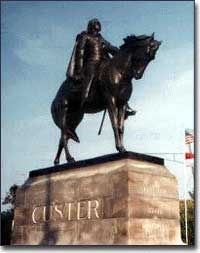

The Statue is entitled "Sighting the Enemy." It depicts General Custer at Gettysburg on July 3rd, 1863. On that date Custer led the famed Michigan Brigade to victory over J.E.B. Stuart, despite Stuart's numerical superiority

Little Big Horn

Custer was perhaps the most flamboyant and brash officer in the United States Army. He was confident that his technologically superior troops could contain the Native American fighters. Armed with new weapons of destruction such as the rapid-firing Gatling gun, Custer and his soldiers felt that it was only a matter of time before the Indians would surrender and submit to life on a smaller reservation. Custer hoped to make that happen sooner rather than later.

His orders were to locate the Lakota encampment in the Big Horn Mountains of Montana and trap them until reinforcements arrived. But the prideful Custer sought to engage the Lakota on his own.

On June 25, 1876, he discovered a small Indian village on the banks of the Little Big Horn River. Custer confidently ordered his troops to attack, not realizing that he was confronting the main Lakota and Cheyenne encampment. A large warrior force (most estimates range from 1200-1500) led by Crazy Horse descended upon Custer's regiment, and within hours about a third of the

The victory was brief for the warring Lakota. The rest of the United States regulars arrived and chased the Lakota for the next several months. By October, much of the resistance had ended. Crazy Horse had surrendered, but Sitting Bull and a small band of warriors escaped to Canada. Eventually they returned to the United States and surrendered because of hunger.

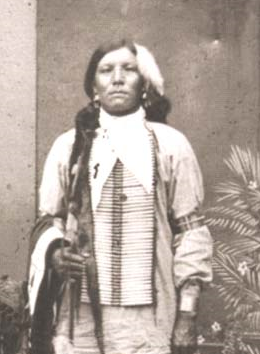

Is this really Crazy Horse? According to most historians, the great Lakota warrior never allowed his picture to be taken. While no images of Crazy Horse have been universally proved as the real deal, this tin-type has been claimed authentic by the Oglala Lakota Tribal Council.

Is this really Crazy Horse? According to most historians, the great Lakota warrior never allowed his picture to be taken. While no images of Crazy Horse have been universally proved as the real deal, this tin-type has been claimed authentic by the Oglala Lakota Tribal Council.Reactions Back East

Custer's Last Stand caused massive debate in the East. War hawks demanded an immediate increase in federal military spending and swift judgment for the noncompliant Lakota.

Critics of United States policy also made their opinions known. The most vocal detractor, Helen Hunt Jackson, published A Century of Dishonor in 1881. This blistering assault on United States Indian policy chronicled injustices toward Native Americans over the past hundred years.

The American masses, however, were unsympathetic or indifferent. A systematic plan to end all native resistance was approved, and the Indians of the West would not see another victory like the Little Big Horn.