25d. The First American Factories

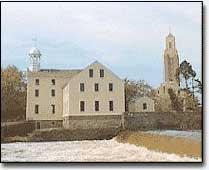

Slater Mill, founded in 1793 by Samuel Slater, is now used as a museum dedicated to textile manufacturing.

There was more than one kind of frontier and one kind of pioneer in early America.

While many people were trying to carve out a new existence in states and territories continually stretching to the West, another group pioneered the American Industrial Revolution. They developed new, large forms of business enterprise that involved the use of power-driven machinery to produce products and goods previously produced in the home or small shop. The machinery was grouped together in factories.

Part of the technology used in forming these new business enterprises came from England, however, increasingly they came from American inventors and scientists and mechanics.

Although the Lowell mills had better conditions than British textile mills, workers still suffered long hours and excessive restrictions on their activities.

The first factory in the United States was begun after George Washington became President. In 1790, Samuel Slater, a cotton spinner's apprentice who left England the year before with the secrets of textile machinery, built a factory from memory to produce spindles of yarn.

The factory had 72 spindles, powered by by nine children pushing foot treadles, soon replaced by water power. Three years later, John and Arthur Shofield, who also came from England, built the first factory to manufacture woolens in Massachusetts.

From these humble beginnings to the time of the Civil War there were over two million spindles in over 1200 cotton factories and 1500 woolen factories in the United States.

|

Dear Father, I received your letter on Thursday the 14th with much pleasure. I am well, which is one comfort. My life and health are spared while others are cut off. Last Thursday one girl fell down and broke her neck, which caused instant death. She was going in or coming out of the mill and slipped down, it being very icy. The same day a man was killed by the [railroad] cars. Another had nearly all of his ribs broken. Another was nearly killed by falling down and having a bale of cotton fall on him. Last Tuesday we were paid. In all I had six dollars and sixty cents paid $4.68 for board. With the rest I got me a pair of rubbers and a pair of 50 cent shoes. Next payment I am to have a dollar a week beside my board... I think that the factory is the best place for me and if any girl wants employment, I advise them to come to Lowell. -Excerpt from a Letter from Mary Paul, Lowell mill girl, December 21, 1845. | ||

From the textile industry, the factory spread to many other areas. In Pennsylvania, large furnaces and rolling mills supplanted small local forges and blacksmiths. In Connecticut, tin ware and clocks were produced. Soon reapers and sewing machines would be manufactured.

The invention of interchangeable parts allowed factories to create clocks like this one in mass quantities.

At first, these new factories were financed by business partnerships, where several individuals invested in the factory and paid for business expenses like advertising and product distribution.

Shortly after the War of 1812, a new form of business enterprise became prominent — the corporation. In a corporation, individual investors are financially responsible for business debts only to the extent of their investment, rather than extending to their full net worth, which included his house and property.

First used by bankers and builders, the corporation concept spread to manufacturing. In 1813, Frances Cabot Lowell, Nathan Appleton and Patrick Johnson formed the Boston Manufacturing Company to build America's first integrated textile factory, that performed every operation necessary to transform cotton lint into finished cloth.

Over the next 15 years they charted additional companies in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Others copied their corporation model and by 1840 the corporate manufacturer was commonplace.

Lowell and his associates hoped to avoid the worst evils of British industry. They built their production facilities at Massachusetts. To work in the textile mills, Lowell hired young, unmarried women from New England farms. The "mill girls" were chaperoned by matrons and were held to a strict curfew and moral code.

Although the work was tedious (12 hours per day, 6 days per week), many women enjoyed a sense of independence they had not known on the farm. The wages were about triple the going rate for a domestic servant at the time.

The impact of the creation of all these factories and corporations was to drive people from rural areas to the cities where factories were located. This movement was well underway by the Civil War. During the 1840s, the population of the country as a whole increased by 36%. The population of towns and cities of 8,000 or more increased by 90%. With a huge and growing market, unconstrained by European traditions that could hamper their development, the corporation became the central force in America's economic growth.