19c. Two Parties Emerge

The State House in Boston was designed by Charles Bullfinch, who also designed the Capitol in Washington D.C.

The election of 1796 was the first election in American history where political candidates at the local, state, and national level began to run for office as members of organized political parties that held strongly opposed political principles.

This was a stunning new phenomenon that shocked most of the older leaders of the Revolutionary Era. Even Madison, who was one of the earliest to see the value of political parties, believed that they would only serve as temporary coalitions for specific controversial elections. The older leaders failed to understand the dynamic new conditions that had been created by the importance of popular sovereignty — democracy — to the American Revolution. The people now understood themselves as a fundamental force in legitimating government authority. In the modern American political system, voters mainly express themselves through allegiances within a competitive party system. 1796 was the first election where this defining element of modern political life began to appear.

The two parties adopted names that reflected their most cherished values. The Federalists of 1796 attached themselves to the successful campaign in favor of the Constitution and were solid supporters of the federal administration. Although Washington denounced parties as a horrid threat to the republic, his vice president John Adams became the de facto presidential candidate of the Federalists. The party had its strongest support among those who favored Hamilton's policies. Merchants, creditors and urban artisans who built the growing commercial economy of the northeast provided its most dedicated supporters and strongest regional support.

This mural, located at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., represents Thomas Jefferson's views on the necessity of education.

The opposition party adopted the name Democratic-Republicans, which suggested that they were more fully committed to extending the Revolution to ordinary people. The supporters of the Democratic-Republicans (often referred to as the Republicans) were drawn from many segments of American society and included farmers throughout the country with high popularity among German and Scots-Irish ethnic groups. Although it effectively reached ordinary citizens, its key leaders were wealthy southern tobacco elites like Jefferson and Madison. While the Democratic-Republicans were more diverse, the Federalists were wealthier and carried more prestige, especially by association with the retired Washington.

The 1796 election was waged with uncommon intensity. Federalists thought of themselves as the "friends of order" and good government. They viewed their opponents as dangerous radicals who would bring the anarchy of the French Revolution to America.

The Democratic-Republicans despised Federalist policies. According to one Republican-minded New York newspaper, the Federalists were "aristocrats, endeavoring to lay the foundations of monarchical government, and Republicans [were] the real supporters of independence, friends to equal rights, and warm advocates of free elective government."

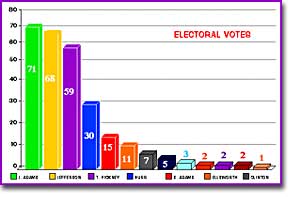

This chart depicts the electoral vote distribution for the election of 1796. John Adams (green) edged out Thomas Jefferson (yellow) for the Presidency, with Thomas Pinckney (purple) and Aaron Burr (blue) leading the runners-up. Jefferson's second-place earned him the Vice Presidency.

Clearly there was little room for compromise in this hostile environment.

The outcome of the presidential election indicated the close balance between the two sides. New England strongly favored Adams, while Jefferson overwhelmingly carried the southern states. The key to the election lay in the mid-Atlantic colonies where party organizations were the most fully developed. Adams ended up narrowly winning in the electoral college 71 to 68. A sure sign of the great novelty of political parties was that the Constitution had established that the runner-up in the presidential election would become the vice president.

John Adams took office after a harsh campaign and narrow victory. His political opponent Jefferson served as second in command.