Whitemarsh: Part 8 of 8

December 7, 1777

On the 7th, Washington discovered Howe shifting his troops toward Edge Hill where Daniel Morgan's riflemen were posted. This was the left-center of the American position. Morgan, along with Colonel Gist's Maryland troops assaulted the British 1st Light Infantry in guerrilla fighting. Using trees and rocks as cover, the Americans gave the British all they could handle, and "the Battle of Edge Hill" dragged on throughout the day. Ultimately, Cornwallis brought his 33rd Regiment into the action, whereupon Morgan decided it was best to withdraw. Casualties numbered about 40 on both sides.

As Morgan was retreating, Howe began a preplanned probe of the American center. He sent a detachment of British Grenadiers toward the Americans, but Major Baurmeister reported it to be well-defended with "strong abatis," "trenches," and "nine uncovered pieces" of artillery.

Meanwhile, British General "No Flint" Grey was straining to get into the action. Howe instructed Grey to hold his troops until Howe's own troops had been able to advance. So Grey dutifully reined in his Rangers. But since Howe discerned no weakness after probing the American lines, he had been unable to move. Grey, meanwhile, waited past the time he had expected to move, then decided to march on his own.

Accompanied by Light Infantry and Queens Rangers he marched toward the American center. Shortly after starting out, they ran into musketry fire which probably came from the Marylanders retreating from Cornwallis's foray earlier in the day. A new battle began on the edge of Edge Hill, which the Americans got the worst of, suffering over a dozen casualties. Grey continued on.

As he pushed forward, Grey cut off Americans Colonel Joseph Reed and General John Cadwalader from the American line. Reed was rendered helpless after falling from his horse which had been had been shot. He was beset by a host of Hessians bearing barbaric bayonets. Cadwalader drew his sword an prepared to defend his friend to the death.

Just then the cavalry rode in to save the day.

Captain Allen McLane, at the head of a squad of horseman, ordered a charge. The Hessians fled and McLane rescued the two American officers. The Cavalry had saved the day.

Shortly after this, the 2nd Continental Regiment attacked Grey's troops halting the British forward movement. Grey, thinking he was outnumbered and feeling he had accomplished his original goal of softening the American position, withdrew.

As night fell two Hessian regiments were brought in to solidify the British line. All seemed in place for another major engagement the next day.

Come sunrise though, Howe was in no mood to fight. The prior nights had been too cold for his liking. Further, he had used up his two-day supply of provisions. His only real offensive threat appeared to be a very wide flanking movement to the east which many of his officers favored. But Howe thought that the American position was too strong to attempt such a movement. The comforts of city life beckoned the soft general. Thus, on the afternoon of the 8th, the British started marching back to Philadelphia.

American cavalry and foot soldiers were sent at the rear of the retreating British column forcing Jagers to turn around, form on elevations, and shoo the pesky Americans away. Finally, some British cannon blasts convinced the Americans they had chased the British far enough.

Surgeon Albigence Waldo commented:

"We were all chagrin'd [at the British retreat] as we were more willing to chase them in the rear than meet such sulkey dogs in front. We were now remanded back [to quarters] with several draughts of rum in our frozen bellies, which made me glad, and we all fell asleep in our open huts, or experienced the coldness of the night."

Washington rued the turn of events. On December 10th he wrote a report to Congress, stating:

I sincerely wish they had made an attack, as the issue, in all probability, form the disposition of our troops, and the strong situation of our camp, would have been fortunate and happy. At the same time I must add, that treason, prudence, and every principle of policy, forbade us quitting our post to attack them. Nothing but success would have justified the measure; and this could not be expected from their position.

Howe's foray against the Americans at Whitemarsh had gained him nothing. A local Tory could not understand Howe's mindset. He wrote that it seemed "as if the sole purpose of the expedition was to destroy and spread devastation and ruin, to dispose the inhabitants to rebellion be despoiling their property."

The three day campaign had resulted in over 300 casualties. The Americans casualties numbered nearly 100.

Parliament, as displeased as the American Congress with the pace of the war, would soon hear word of yet another futile expedition.

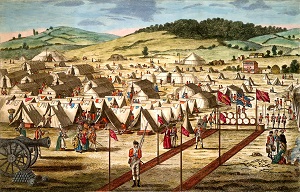

Meanwhile, Washington could not remain at Whitemarsh indefinitely. Though he had held off the British once, there was no guarantee that he could repulse them a second time. Further, Whitemarsh was just too close for comfort to the British in Philadelphia. And Whitemarsh was also not a particularly good location for a winter camp. It was too spread out too hard to supply.

On the 11th, Washington broke camp at Whitemarsh and headed over the Schuylkill yet one more time.

In eight days the American army would wind up at a small village along the Schuylkill — Valley Forge.

Students of the 12th Grade Honors History Class of Philadelphia-Montgomery Christian Academy created this educational website on the Battle of Whitemarsh.

They did a great job. Check it out!