Temple's Diary

A Tale of Benjamin Franklin's Family

In the Days Leading up to The American Revolution

I have not yet related the conversation I had with Uncle Richard after we left the State House on May 10. To my surprise, he had suggested that instead of going home we repair to the City Tavern for a little refreshment. Grandfather, sorry to have so little time for me, had given Uncle Richard some money to treat me to a good time.

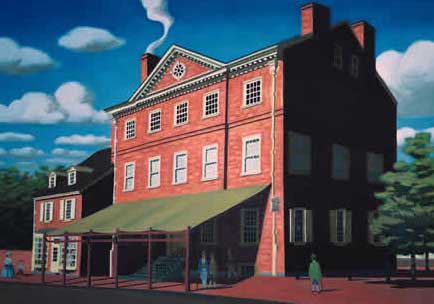

City Tavern

Quite a place, this City Tavern. My well informed companion explained that when it opened, about two years ago, it offered a combination of "club and pub." Club, because it was financed by selling shares to the upper class Philadelphians yearning for a genteel meeting place, and pub, because the atmosphere and fare were modeled on London. It is already famous for being the finest tavern in the colonies, equipped with a spacious room for balls and banquets, or even for concerts and operas. So much for my earlier remark that Philadelphia has no concert hall! This city, I must admit, is much more exciting than I expected.

We sat down and, without consulting me, my uncle ordered two everlasting syllabubs.

— "Two what?"

— "Syllabubs, the favorite treat of Philadelphians."

— "Lucky you!" interjected the waitress, a girl about my age, pretty and blonde under her frilly bonnet. "A syllabub is the best drink in the world."

— "What's in it?"

— "Everything. Lots of thick cream and Rhine wine and sack — that's white wine from Spain — and the juice of Seville oranges and the grated rinds of lemon and quantities of double-refined sugar and a spoonful of orange-flower water." She caught her breath and prepared to tell us how this marvel is put together, preferably in advance, but I stopped listening because she had dimples when she smiled, and suddenly I could think of nothing but those dimples.

She saw me gawking, looked amused, and disappeared.

— "Let's talk," said my uncle. "Is there anything you would like to know?"

— "Yes. Once again, what's happening with my father? Doesn't he want to meet me?"

— "Temple, it is time you understood that men in public life like to moan and groan that their duties keep them from their families, which is their terrible, terrible fate. But, as soon as circumstances let them go back to those beloved families, all they aspire to do is get themselves once again in the limelight while pretending to pine, of course, for the sweetness of family life. Your father is to deliver a speech on May 15 to the New Jersey Assembly, and then he has to meet with his Council for a few days, after which he will surely come for you and take you away for the summer. You will have the whole summer to get acquainted."

Although Uncle Richard spoke calmly, I thought there was a touch of bitterness in his voice. He will never be a public man; he is a merchant, and not a very successful one at that, if one is to judge by the penny-pinching practices of Aunt Sally.

— "Do you have any idea," I ask, "what my father is going to talk about when he speaks to the Assembly?"

— "He will sing the same old song about his prowess in managing to serve both the King and the Colony at the same time. He will preach reconciliation with the British Empire and probably push the Plan of Union advocated by his friend and ally, Joseph Galloway."

The girl reappeared at that moment with two large bowls and gave me the fuller one, after which she stood there, watching me. How could I bring back the dimples? What should I do? I had to make her laugh. With exaggerated expressions of surprise and delight, I inhaled the frothy top of my syllabub and emitted groans of bliss while she giggled and the dimples returned, more alluring than ever. But alas, she was promptly summoned to another table and we went back to Mr. Galloway.

My uncle explained that Galloway was born into a prominent and well-to-do family. He had met my father when they were both in their twenties. It seems that my father, who had distinguished himself in the French and Indian War and planned a military career, was in danger of becoming an idle and frivolous young man after the peace treaty was signed, a prospect that Grandfather could not stand to contemplate. Galloway, who had studied law, was entrusted with teaching its basics to William in preparation for further studies at one of the Inns of Court in London.

— "Galloway and your father remained close friends and became, so to say, the legal team employed by your grandfather in the course of his political life. They helped the older man in his fight to have the Crown take control of Pennsylvania, thus taking power away from the descendants of William Penn, those Proprietors whom Dr. Franklin had come to detest. Even though Galloway is devoid of interest in scientific matters and has a cold and haughty personality, your grandfather feels that he brought important assets to the partnership: his seriousness, his impeccable social credentials, his knowledge, and his talent as an orator. For many years, while Dr. Franklin was in England, Galloway served him well as a trusted lieutenant across the Ocean, but now..."

"But now?" Uncle Richard was searching for the right words. "But now, he is the victim of his unbending nature. He has done very well, politically speaking: member of the Pennsylvania Assembly for 20 years, its Speaker for nine — and that is a position of great power. He headed the Pennsylvania delegation to the first Continental Congress. While he recognized that the colonies had some reason to resent the restrictions imposed by England on American commerce, and also to resent the taxes imposed by Parliament, his solution for reconciliation was rejected. He is a man who cannot accept defeat, and my hunch is that any day now he may walk out of the current Congress."

(Uncle Richard was right when he predicted this on May 10; Galloway stalked out two days ago, on the 12th.)

— "And my father?"

— "In your father's eyes, both last year's Continental Congress and the one which we saw convene today are illegal. What your father would like to see is American representation in Parliament right in London. It is an attractive idea but unlikely to be adopted. Well-trained lawyers that they are, your father and Galloway see everything in legalistic terms. They are no longer in touch with the feelings of a growing part of the population; they live in a world of theory."

— "And Grandfather?"

— "I think that in his mind he understood long ago that reconciliation is a hopeless cause, but in his heart he still nurtures a tiny hope, because he has loved England so much. Unlike many other people, he believes that only stiff resistance can produce a compromise. I remember him quoting an Italian proverb: `He who turns himself into a sheep is eaten by the wolf.' And that is why all his energy these days goes into preparing the nation for war. He wants the British to understand that time is running out and that they had better wake up and negotiate in good faith. But what your grandfather has not yet grasped is how far his beloved son and his beloved Galloway have diverged from him, they who used to follow all his instructions unquestioningly. I am afraid, Temple, that he is in for a terrible disappointment."

My uncle then stood up, shook my hand, and said he had enjoyed talking to me, man to man. The thought of my grandfather possibly being so badly hurt in the near future gave me a heavy heart, but then I started thinking of ways to see the dimpled girl again, and I felt better. I am only 15, after all.