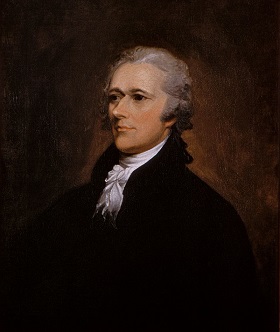

Alexander Hamilton

James Monroe, Henry Lee, John Marshall, Alexander Hamilton, and Marquis de Lafayette were some of the Continental Army officers who served George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Of these rising stars, Alexander Hamilton overcame the greatest odds, including impoverishment and illegitimacy, in obtaining his position as aide-de-camp to General Washington. For approximately the next twenty years, Hamilton and Washington would work with each other during the Revolutionary War, the framing of the Constitution, and Washington's Presidency of the United States. The period of 1777-1778, however, pivotal to the success of the Continental Army, and ultimately that of the Continental Congress, also was important for Hamilton, for during this time, he rapidly proved his worth on a national basis.

Alexander Hamilton was born on the West Indian Island of Nevis. His father, of Scottish ancestry, remained in Scotland during Hamilton's childhood due to a debt, forcing his mother to rely on friends and relatives for financial support. Around the age of ten the family moved to the nearby island of St. Croix where his mother died soon after. Friends and relatives took an interest in the future of the young Hamilton by encouraging him to work as a mercantile clerk and to read and write, activities at which he excelled despite his lack of proper schooling. Hamilton's formal education began after Reverend Hugh Knox, a Presbyterian minister, gave a sermon so inspiring that Hamilton wrote a description of it for the Royal-Danish American Gazette. When a group of readers found out that the words were those of an under-privileged fifteen-year-old they decided to sponsor his way to the American Colonies to receive his first formal education.

Hamilton attended King's College (now Columbia University) located outside of what was then 18th century New York City. In this prime location, Hamilton was surrounded by talk of rebellion, as well as arguments against it. Events and issues were leading up to the Battle of Lexington and Concord in but a few months; although outright rebellion and war against the mother country was unthinkable, a war of words was reality. The radical politics of New York (and other colonies) were expressed by way of pamphlets. A particular New York Loyalist in favor of England's crown policy, known as 'the Farmer' in his sympathetic writings, favored royal British authority in the American colonies and denounced all actions of a colonial American congress. 'The Farmer' received several responses from Hamilton and other rebellious spirited Whigs. 'Friend to America,' an assumed name of Hamilton's, responded to 'the Farmer' in his pamphlet. He defended the American congress, writing in reference to members of parliament on December 15, 1774, "...That they are enemies to the rights of mankind is manifest, because they wish to see one part of their species enslaved by another. That they have an invincible aversion to common sense is apparent in many respects: They endeavor to persuade us, that the absolute sovereignty of parliament does not imply our absolute slavery".1 Hamilton continued to write in defense of colonial-American rights throughout the war.

With war pending, Hamilton immersed himself in the study of artillery tactics and military maneuvers. In March of 1776, he joined the New York Artillery, and was recommended for an officer's commission by General Alexander McDougall. He was thereby given the title "Captain of the Provincial Company of Artillery." As noted by a top scholar, "Hamilton's abilities as a conscientious and business-like leader were evident from his earliest days of military service. He not only had to recruit and train his own men; he also had to see that they were fed, clothed, and paid. While many young New Yorkers may have fought the enemy as bravely as Hamilton did, few battled the local authorities so stubbornly to provide for their troops."2 In May of 1776 Hamilton wrote to the New York provincial congress regarding the condition of his men. He was concerned because the men in his company of artillery were not quite at full strength. Hamilton had an additional problem because his men were paid less than other artillery companies and their duties were the same. There was only so much the New York provincial congress could do, however. British and Hessian troops under General William Howe disembarked from Halifax for New York City during the summer of 1776. Meanwhile, General Washington marched his army from Boston, and proceeded to strategically fortify the main waterway approaches to New York City.

Hamilton's New York Artillery Company was used in strategic areas in New York City. Upon losing successive battles in the city of New York, he covered the Continental Army's rear in a number of the withdrawals. Initially, Hamilton's company was placed at Fort George on the waterfront of Manhattan. During the Battle of White Plains Hamilton placed his cannon in such a place as to turn back a significantly sized Hessian advance. This decisive movement left a good impression of Hamilton among the American high command and delayed in part the British offensive, thus giving the Continental Army preciously needed time to perform an orderly retreat. When the Continental Army evacuated New York City, Forts Washington and Lee fell to a victorious British force. With much of the army's enlistment expiring at the beginning of and throughout December, Washington led a desperate retreat through New Jersey and into Pennsylvania. Hamilton's artillery company was specifically selected to cover the hasty retreat from New Brunswick, New Jersey.

The victory at the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776, distinguished Hamilton in a Continental Army that gained a newfound hope in fending off the British incursion into Philadelphia. General Howe posted troops throughout New Jersey to liberate Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in 1777 from rebel leaders. Washington recognized Howe's tactic in attempting to demoralize the cause, and found it absolutely necessary to establish a newfound hope with his army. During the night of the surprise attack on Hessian soldiers at Trenton, Hamilton's skill and experience were crucial. Serving in Lord Stirling's brigade, Captain Hamilton and Captain Forrest's artillery companies were assigned to cover King Street and the parallel Queen Street. Hamilton and Forrest were well equipped; each had two six-pound cannon, while Forrest also had a pair of Howitzers. With both streets covered by the artillery, Hessian commander Colonel Johann Rall, decided to form up his infantry and artillery and march on the Americans from King Street. "No sooner had the Hessians stepped off, however, when the round-shot from Hamilton's battery tore through their ranks," according to a recent book entitled Battles of the Revolutionary War.3 The Hessians under Rall retreated in the opposite direction, and many ended up surrendering because of the effective rounds discharged from Hamilton's artillery company. General Hugh Mercer placed his American infantry between houses from the direction of Queen Street on the right flank of Colonel Rall's Hessians. The effective rounds discharged from Hamilton's artillery combined with the musketry of Mercer's troops, and devastated the Hessian ranks with casualties. This caused a general retreat among the Hessian troops; many of them were enfolded and forced to surrender to the victorious Continentals.

After Hamilton's gallantry and heroic accomplishment displayed at the crucial engagement at Trenton, he was appointed an aide to General Washington. In this position his writing skills and keen sense of judgement would prove essential to the highest command in the army. The 1777 winter encampment at Morristown, New Jersey, found Hamilton with an army of well under 10,000. The army, however, was reinforced steadily as the winter progressed into spring. During this time Hamilton recorded, "the many deserters coming in from the enemy showed them to be in desperate straits... Since the possibility that the French might enter the war in Europe would disincline the British from sending reinforcements overseas"4. General Howe's army made a feint into northern New Jersey in the spring of 1777 to draw the Continental Army out of the highlands of Morristown. Nevertheless, it would be weeks before it became a certainty that Howe's intention was Philadelphia. During that time, Hamilton received on-the-job training and became accustomed to the cramped living style as a part of General Washington's staff.

While the Continental Army awaited the approach of General Howe and the British Army in Wilmington, Delaware, Hamilton described the atmosphere before the Battle of Brandywine. On September 1, 1777, he wrote of General Howe's slovenly movements, the Continental Army's morale, and of the surrounding landscape. "He still lies there [Greys Hill, Pennsylvania] in a state of inactivity; in a great measure I believe from the want of horses, to transport his baggage and stores. It seems he sailed with only about three weeks provendor and was six at sea. This has occasioned the death of a great number of his horses, and has made skeletons of the rest. He will be obliged to collect a supply from the neighboring country before he can move... This country does not abound in good posts. It is intersected by such an infinity of roads, and is so little mountainous that it is impossible to find a spot not liable to capital defects. The one we now have is all things considered the best we could find, but there is no great depindence [sic] to be put on it. The enemy will have Philadelphia, if they dare make a bold push for it, unless we fight them a pretty general action. I opine we ought to do it, and that we shall beat them soundly if we do. The militia seem pretty generally stirring. Our army is in high health & spirits. We shall I hope have twice the enemy's numbers. I would not only fight them, but I would attack them; for I hold it an established maxim, that there is three to one in favour of the party attacking..."5 Among the dispatches arriving at the Ring House were conflicting reports concerning the right flank of the Continental Army. The secretive movements made by Howe and Cornwallis had couriers bringing reports in all morning. One of Hamilton's duties at the home of Benjamin Ring was to establish the immediate importance of incoming dispatches. After deciding to reinforce the right flank of the Continental Army with Nathanael Greene's Brigades, General Washington and Lafayette, along with Washington's staff, rode along with Greene's troops. Upon the scene of the battle they tried to rally the Continentals of Stephen's and Stirling's divisions. The American stand at Brandywine Creek almost proved fatal, but there was no other alternative for Washington. During the nine months that remained in the 1777-78 Philadelphia Campaign, Hamilton was deployed on missions of major importance on the request of General Washington.

When General Washington decided to keep his army between Howe and the Continental Army's supply line deeper in Pennsylvania, he sent Hamilton on a mission to destroy a supply of flour and prevent other supplies from falling into British hands as they marched toward Philadelphia. Hamilton now led a group of eight cavalrymen which included Captain Henry Lee, and was about to burn the mill at the small village of Valley Forge when two sentries fired warning shots from their posts. The force of British Cavalry, largely outnumbering Hamilton's force, at first chased Captain Lee who took flight across the millrace with a pair of mounted American cavalry. The British dragoons gave up the chase with Lee and went after Hamilton. While Hamilton attempted to cross the Schuylkill River in a scow, the green-coated dragoons fired numerous volleys at him and the remainder of his party. The musketry wounded one man, killed another, and crippled Hamilton's horse. Hamilton had no choice but to swim to the other side of the river whereafter he wrote to John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress, the British had potential to be in Philadelphia that evening. Upon returning to Washington's headquarters, Hamilton was chagrined to find out that he had been given up for a casualty by word of Lee. Meanwhile, the Continental Congress and Philadelphia patriots were in a panic, securing valuables, and leaving the city.

The British did not enter the city that night, or within even within the next week. Hamilton's next mission was to go into Philadelphia and obtain shoes, blankets, clothing, and other important supplies for the Continental Army. On September 26, the British under Howe finally marched into Philadelphia. Hamilton's missions were not completely over, however, and after the Battle of Germantown was fought in October 1777, he was sent north to New York. General Horatio Gates was the recent victor of Saratoga, where he defeated British General "Gentleman Johnny" Burgoyne. Gates was reluctant to send reinforcements to Washington, and when Gates would not acknowledge Washington's request through dispatch, Hamilton was hurried into negotiations. By the time reinforcements had arrived to bolster Washington's numbers, Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer had fallen into British hands, and the Royal Navy had complete access to the Delaware River and could supply the occupying army at Philadelphia shipping ports. Hamilton would spend the remainder of the winter at Valley Forge in Washington's Headquarters at one of the homes of Isaac Potts, next to where he experienced the near deadly encounter with green-coated British dragoons the previous autumn.

After the trying winter at Valley Forge and the formal alliance with France, Hamilton observed the Continental Army as it became nearly victorious over the Redcoats at the Battle of Monmouth. Hamilton and Lafayette were close behind General Washington on the battle line as he rallied the Continentals to near victory. Hamilton was described during the battle as "...incessant in his endeavors during the day in reconnoitering the enemy, in rallying, and in charging..."6 During the remainder of the time he served the position of aide-de-camp, Washington would not allow Hamilton to independently command a force of troops, because it would be unfair to other Continental Army officers who surpassed him in seniority. General Washington and Colonel Hamilton had a falling out in the spring of 1781, and Hamilton resigned as an aide to the Commander-in-Chief. Eventually he was given an independent command and during Yorktown campaign, he commanded the capture of a strategic fortification (redoubt #10), at the siege of Yorktown, Virginia.

Following the capitulation of General Cornwallis and his army at Yorktown, Hamilton was appointed a member of Congress. He worked closely with fellow New Yorker, Gouveneur Morris, in financing the fledgling national government. Hamilton's steady work with the colonial assembly in congress sums up his wartime activity. His rapid advancement from the Caribbean islands, to college in New York, and the experience he obtained in the Continental Army (especially as an aide to Washington) continued with his tremendous influence during the framing of the Constitution, and beyond. The extraordinary achievements he made during the War for American Independence impressed not a few. Alexander Hamilton's contributions to the United States during this early period will not be forgotten any time soon.

Andrew Ronemus

- The Founding Fathers. Alexander Hamilton: A Biography in His Own Words. New York: Newsweek, 1973.

- ibid

- Wood, W.J. Battles of the Revolutionary War. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1990.

- Flexner, James Thomas. The Young Hamilton. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1978.

- Schmucker, Samuel M. The Life and Times of Alexander Hamilton. Philadelphia: John E. Potter and Company, 1856.

- ibid